Working Group to Inform the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) Steering Committee on Modernization of Price Review Process Guidelines

Final Report - March 2019

PDF version (4.17 MB)

Table of Contents

-

Section 1: Criteria for classifying medicines as ‘Category 1’

-

Section 2: Supply-side cost effectiveness thresholds

-

Section 3: Multiple indications

-

Section 4: Accounting for uncertainty

-

Section 6: Market size factor

-

Appendix 1: Conceptual Framework

-

Appendix 2: Materials Presented at Meetings of the Working Group

-

Appendix 3: ‘On The Record’ Comments

-

Appendix 4: Terms of Reference

-

Appendix 5: Policy Intent

-

Appendix 8: External Review of Draft Report

Purpose

The purpose of this report is to summarise the deliberations and recommendations of the Working Group to Inform the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) Steering Committee on Modernization of Price Review Process Guidelines.

Introduction

In June 2018, the PMPRB established a Steering Committee on Modernization of Price Review Process Guidelines (hereafter the ‘Steering Committee’). Its mandate was to assist the PMPRB in synthesizing stakeholder views on key technical and operational modalities of the PMPRB’s new draft Guidelines.

In July 2018, the PMPRB established the Working Group to Inform the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) Steering Committee on Modernization of Price Review Process Guidelines (hereafter the ‘Working Group’). Its mandate was to inform the Steering Committee on certain issues that the Steering Committee believed would benefit from the review of experts in health technology assessment and other economic and scientific matters.

This report provides a summary of the Working Group’s deliberations and recommendations.

Membership

The chair of the Working Group was Dr Mike Paulden (University of Alberta).

Twelve individuals sat as members of the Working Group (listed alphabetically):

- Sylvie Bouchard (INESSS)Footnote 1 [represented by Patrick Dufort and Marie-Claude Aubin];

- Dr Chris Cameron (Dalhousie University and Cornerstone Research Group);

- Dr Doug Coyle (University of Ottawa);

- Don Husereau (University of Ottawa);

- Dr Peter Jamieson (University of Calgary);

- Dr Frédéric Lavoie (Pfizer Canada) (Industry Representative);

- Karen Lee (University of Ottawa and CADTH)Footnote 2;

- Dr Christopher McCabe (University of Alberta and Institute of Health Economics);

- Dr Stuart Peacock (Simon Fraser University and BC Cancer Agency);

- Maureen Smith (Patient);

- Geoff Sprang (Agmen) (Industry Representative);

- Dr Tania Stafinski (University of Alberta).

Two individuals sat as observers of the Working Group:

- Edward Burrows (Innovation, Science and Economic Development);

- Nelson Millar (Health Canada).

One individual acted as an external reviewer of the Working Group’s draft report:

- Dr Mark Sculpher (University of York).

An additional individual from CADTH, Dr Tammy Clifford, accepted an invitation to sit as a member of the Working Group but did not participate in the Working Group’s deliberations. Dr Clifford also did not contribute towards, or vote on, the Working Group’s recommendations.

Terms of Reference

The Terms of Reference (Appendix 4) required that the Working Group examine and make recommendations with respect to specific considerations and questions within the following six ‘areas of focus’:

- Options for determining what medicines fall into ‘Category 1’

- A Category 1 medicine is one for which a preliminary review of the available clinical, pharmacoeconomic, market impact, treatment cost and other relevant data would suggest is at elevated risk of excessive pricing.

- The following criteria have been identified as supporting a Category 1 classification:

- The medicine is ‘first in class’ or a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options

- The medicine’s opportunity cost exceeds its expected health gain

- The medicine is expected to have a high market impact

- The medicine has a high average annual treatment cost

- Should other criteria be considered? What are the relevant metrics for selecting medicines that meet the identified criteria and what options exist for using these metrics?

- Application of supply-side cost effectiveness thresholds in setting ceiling prices for Category 1 medicines

- Potential approaches for implementing a price ceiling based on a medicine’s opportunity cost.

- Potential approaches for allowing price ceilings above opportunity cost for certain types of medicines (e.g. pediatric, rare, oncology, etc.)

- Medicines with multiple indications

- Options for addressing medicines with multiple indications (e.g. multiple price ceilings or a single ceiling reflecting one particular indication).

- Accounting for uncertainty

- Options for using the CADTH and/or INESSS reference case analyses to set a ceiling price.

- Options for accounting for and/or addressing uncertainty in the point estimate for each value-based price ceiling.

- Perspectives

- Options to account for the consideration of a public health care system vs societal perspective, including the option of applying a higher value-based price ceiling in cases where there is a ‘significant’ difference between price ceilings under each perspective.

- How to define a ‘significant’ difference in price ceilings between each perspective.

- Application of the market size factor in setting ceiling prices

- Approaches to derive an appropriate affordability adjustment to a medicine’s ceiling price based on an application of the market size and GDP factors (e.g. based on the US ‘ICER’ [Institute for Clinical and Economic Review] approach).

Under the Terms of Reference, the Steering Committee had the opportunity to specify additional areas of focus for the Working Group. The Steering Committee did not identify any additional areas of focus for the Working Group to consider.

Objections

The industry members (Frédéric Lavoie and Geoff Sprang) repeatedly raised objections to what they regarded as the “very narrow boundaries” established by the Terms of Reference.

Among these objections was a concern that the Working Group was not permitted to examine whether the PMPRB should be considering economic factors as part of the proposed reforms, nor any logistical or operational issues associated with implementation of the proposed reforms.

The industry members also stated that, as representatives of BIOTECanada and Innovative Medicines Canada (IMC), they “do not support the inclusion of proposed economic factors in a quasi-judicial price ceiling regulatory methodology given the uncertainty these factors would introduce, their practical challenges and complexity of implementation”, arguing that “the government’s regulatory objectives can be achieved by much simpler, more transparent and predictable mechanisms that will ensure access to necessary prescription medications while achieving the regulatory “bright lines” which PMPRB has recognized as a key consideration”.

The industry members submitted a number of ‘on the record’ comments to the chair regarding these and other matters, all of which are reproduced verbatim in Appendix 3.1 to 3.5.

The patient member (Maureen Smith) also submitted ‘on the record’ comments regarding these and other matters, which are reproduced verbatim in Appendix 3.6.

Policy intent

The PMPRB provided the Working Group with a copy of the Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations, as published in Canada Gazette Part I: Vol 151 (2017).

This document includes a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement and the Proposed Regulatory Text and is reproduced in Appendix 5.1.

The Working Group was instructed by the PMPRB to make its considerations and recommendations on the assumption that the Regulations Amending the Patented Medicines Regulations will remain unchanged in their final publication.

The Working Group therefore considered the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement and Proposed Regulatory Text as providing a definitive statement of the policy intent with respect to the proposed regulations.

In addition, the PMPRB provided three supporting documents to aid the Working Group in understanding the policy intent:

- PMPRB Guidelines Scoping Paper (Appendix 5.2);

- PMPRB Framework Modernization Presentation (Appendix 5.3);

- PMPRB Short Primer (Appendix 5.4).

The chair sought clarity from the PMPRB in cases where the Working Group was not clear about any aspect of the policy intent.

Process and procedure

The Working Group was convened in July 2018 and met three times in-person and multiple times via teleconference between July 2018 and February 2019:

- 26 July 2018 (all day in-person meeting);

- 22 and 24 August 2018 (1 hour teleconference for each of six areas of focus);

- 24 August 2018 (2 hour teleconference);

- 25 September 2018 (2 hour teleconference);

- 12 October 2018 (all day in-person meeting);

- 28 November 2018 (2 hour teleconference);

- 5 February 2019 (all day in-person meeting).

The Working Group was originally intended to report in October 2018, but this timeline was extended until March 2019.

Detailed meeting notes were taken by PMPRB staff and emailed to the chair following each meeting. A draft summary of these notes was circulated among Working Group members. In order to encourage a frank and open discussion, the chair committed to not identifying members alongside their comments in the Working Group’s report, unless requested to by the member. Members were permitted to provide ‘on the record’ comments regarding any matters of concern.

One week prior to the final in-person meeting on 5 February 2019, the chair circulated a draft ‘Conceptual Framework’ to all members. A revised version is reproduced in Appendix 1.

The purpose of this ‘Conceptual Framework’ was to guide members in making consistent recommendations across all six areas of focus, while respecting the policy intent and the range of views expressed by members throughout the Working Group’s deliberations.

On 7 February 2019, the chair circulated a set of ‘draft potential recommendations’. Members were invited to submit comments or suggested modifications until 15 February 2019.

On 18 February 2019, the chair circulated a draft report of the Working Group’s deliberations to all members and the external reviewer, including a final set of ‘potential recommendations’.

Under the Terms of Reference, recommendations were determined by a vote of the members, with the chair having the casting vote in the event of a tie. Members were asked to vote on the potential recommendations using an online form, and the full results of the vote were shared with all members. The chair committed not to identify members who voted ‘in favour’ or ‘against’ each potential recommendation in the Working Group’s final report.

Comments on the draft report, and votes on the potential recommendations, were accepted until 1 March 2019. The final report was submitted to the PMPRB on 6 March 2019.

1: Criteria for classifying medicines as ‘Category 1’

1.1 Terms of Reference

Within this area of focus, the Terms of Reference required the Working Group to examine and make recommendations with respect to the following considerations and questions:

A Category 1 medicine is one for which a preliminary review of the available clinical, pharmacoeconomic, market impact, treatment cost and other relevant data would suggest is at elevated risk of excessive pricing.

The following criteria have been identified as supporting a Category 1 classification:

- The medicine is ‘first in class’ or a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options;

- The medicine’s opportunity cost exceeds its expected health gain;

- The medicine is expected to have a high market impact;

- The medicine has a high average annual treatment cost.

Should other criteria be considered? What are the relevant metrics for selecting medicines that meet the identified criteria and what options exist for using these metrics?

The chair clarified with the PMPRB whether the Terms of Reference permitted the Working Group to consider whether any of the criteria should be omitted. The PMPRB confirmed that such a consideration was within the purview of the Working Group.

1.2 Policy Intent

The PMPRB Guidelines Scoping Paper includes the following statement which provides context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“The second part of the framework consists of a screening phase which would classify new patented drugs as either high or low priority based on their anticipated impact on Canadian consumers, including individual patients and institutional payers (e.g., public and private drug plans). At this stage in the process, the PMPRB would consider whether the drug is first in class, has few or no therapeutic alternatives, provides significant therapeutic improvement over existing treatment options, is indicated for a condition that has a high prevalence in Canada, is a high cost drug (i.e. an average annual cost higher than a GDP-based threshold) or is classified as a high priority drug by other agencies/regulators in the health care system (such as the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) or Health Canada) because of unmet medical need. Drugs that appear to be high priority based on these screening factors would be subject to automatic investigation and a comprehensive review to determine whether their price is potentially excessive.”

(p.6, emphasis added)

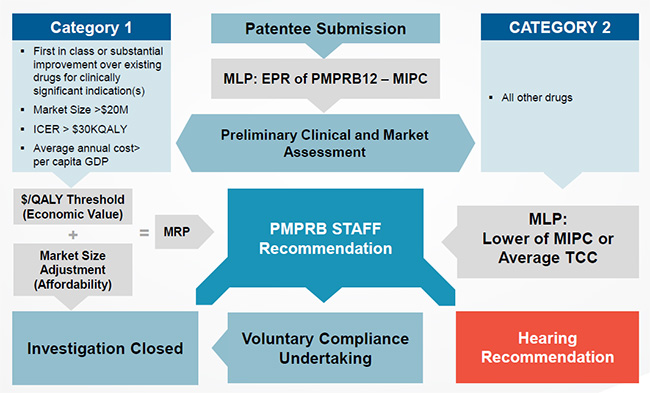

The PMPRB Framework Modernization Presentation includes the following slide which provides context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

Proposed PRICE Review Schematic

Figure description

Slide 11 is a work-flow diagram of how the proposed PRICE review process will function.

The first step in the process is the receipt of a Patentee submission for a new patented drug which is represented the box in the center of the diagram.

From there, a Maximum List Price (MLP) is established. This is done through an external price review based on the PMPRB12 countries, as proposed in the amendments to the Regulations. The MLP is established as the median of an international price comparison (MIPC) of the countries in the PMPRB12. This is represented in the box below the receipt of the Patentee submission.

In next step in the process, represented by the box below, a Preliminary Clinical and Market Assessment is conducted. Based on the results of this assessment the drug is categorised as one of two categories:

- A Category 1 drug, the attributes of which are included in the box to the left, indicated by an arrow pointing to the box.

- A Category 2 drug, all other drugs that do not have a Category 1 classification. This is represented by the box to the right.

Starting from the top left, Category 1 drugs are those that are either:

- First in class or offer a substantial improvement over existing drugs for clinically significant indication(s)

- Have a Market Size greater than $20M

- Expected to diminish population health ($/QALY>$30K)

Once a drug is classified as a Category 1 drug, it moves down to the box that represents an Economic Value test. To pass this test, the drug’s cost effectiveness value must be below a certain $/QALY threshold.

If the drug passes the economic value test, it moves to the box below which represents an affordability test, based on a market size adjustment. If the drug fails either the economic value test or affordability test it moves to a central box. The central box represents the PMPRB Staff Recommendation stage.

If the a drug passes both the economic value test and affordability test, it then moves down to the last box on the left and the Investigation is closed.

At the top right is the starting box for Category 2 drugs. For this category the Median International Price is compared to the Average of the Therapeutic Class Comparison. The MLP becomes the lower of the two tests as indicated in the second box on the right. From here, the drug moves to the centre box, PMPRB Staff Recommendation stage.

At the PMPRB Staff Recommendation stage, staff review the merits of each drug on a case-by-case basis and make a recommendation to the Board.

At this stage, PMPRB Staff make one of the following recommendations: Close Investigation as indicated in the box at the bottom left; proceed to a Hearing as indicated by the box at the bottom right; or agree to a Voluntary Compliance Undertaking as indicated in the bottom center box.

From the Voluntary Compliance Undertaking box, the drug moves to the Investigation Closed stage on the bottom left once the VCU has been signed.

1.3 Summary of Deliberations

There was widespread agreement among members of the Working Group that not all medicines require the same extent of review, and that a ‘risk-based’ approach is desirable.

However, there was debate among the Working Group regarding the criteria that should be used by the PMPRB to identify medicines at elevated risk of excessive pricing (‘Category 1’).

1.3.1 No other criteria considered

Under the Terms of Reference, the Working Group was required to examine and make recommendations regarding whether “other criteria” should be considered by the PMPRB.

No members of the Working Group proposed that any other criteria be considered beyond those specified in the Terms of Reference.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.1: The Working Group does not recommend any additional criteria beyond those specified in the Terms of Reference.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.2 ‘Substantial improvement over existing options’

A number of members expressed concern about the wording of Criterion A (‘The medicine is ‘first in class’ or a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options’).

Although there was general agreement that ‘first in class’ medicines should be classified as ‘Category 1’, many members questioned why medicines that offer “a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options” should be classified as ‘Category 1’ if none of the other criteria are met.

Concern was raised by some members that inclusion of this term might penalize manufacturers for producing medicines that offer ‘substantial improvement’, disincentivizing their development. Some members questioned whether this would, in turn, undermine the policy intent.

The chair asked the PMPRB to clarify the policy intent behind the inclusion of this term. The PMPRB responded that medicines that offer a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options are more likely to dominate their respective market, increasing the risk of ‘excessive pricing’.

Some members argued that, even if a medicine dominates its market, if the medicine does not have ‘high’ market impact or a ‘high’ average annual treatment cost then the number of patients affected will be relatively small. Within a ‘risk based’ approach to classifying medicines, this might justify excluding the ‘substantial improvement’ term from Criteria A. One member dissented from this position, arguing that the PMPRB has a mandate to protect consumers from ‘excessive prices’, even if the number of patients affected is small.

Members of the Working Group were unable to identify examples of medicines which offer a ‘substantial’ improvement over existing options but would not be considered ‘first in class’ and would not have ‘high’ market impact or a ‘high’ average annual treatment cost. Even if inclusion of the ‘substantial improvement’ term is consistent with the policy objective, this raises the question as to whether its inclusion is redundant, given the presence of these other criteria.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.2: The Working Group recommends that the PMPRB consider whether the wording “substantial improvement over existing options” within Criterion A is redundant or inconsistent with the policy intent, and, if so, remove this from consideration.

Members voted 11 in favour and 1 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.3 ‘Opportunity cost’ criterion

There was widespread agreement that Criterion B (‘The medicine’s opportunity cost exceeds its expected health gain’) should not be considered when classifying medicines as ‘Category 1’.

Some members cited the logistical difficulty of establishing cost-utility estimates for all newly launched medicines, rather than only those classified as Category 1. However, since logistical issues were not within scope of the Terms of Reference, these issues were not considered by the Working Group.

The industry members argued that the PMPRB’s proposed $30,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) threshold is sufficiently low as to capture over 90% of all new medicines, such that classification as ‘Category 1’ would not serve as a useful screening mechanism. A potential response to this specific concern would be to raise the threshold used for screening to a sufficiently high level that a manageable number of new medicines are classified ‘Category 1’.

Another reason for excluding Criterion B, given by some members and consistent with the Conceptual Framework, is that this criterion may be redundant in the presence of the other criteria. If a medicine does not satisfy any of the other criteria - that is, it does not have a ‘high’ average annual cost, does not have ‘high’ market impact, is not ‘first in class’ and does not offer a ‘substantial improvement’ over existing treatment - then the potential loss in consumer surplus that might result from its adoption is limited, regardless of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Under a risk-based approach, it may therefore be better to focus the resources available for assessing ‘Category 1’ medicines on medicines with ‘high’ average annual treatment cost, ‘high’ market impact and/or the potential to dominate their respective market.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.3: The Working Group recommends that Criterion B be removed from consideration.

Members voted 11 in favour and 1 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.4 ‘High average annual treatment cost’

There was disagreement amongst the Working Group regarding Criterion D (‘The medicine has a high average annual treatment cost’), specifically whether ‘high average annual treatment cost’ should be considered in absolute terms or as incremental upon existing treatment.

It was noted that a new medicine could have ‘high average annual treatment cost’, but might replace an existing treatment that also has ‘high average annual treatment cost’, such that the incremental average annual treatment cost is not ‘high’.

Some members noted that, if the existing treatment has ‘high average annual treatment cost’, this increases the risk that the existing treatment is itself considered to be ‘excessively priced’. In such cases, the new medicine may also be considered to be ‘excessively priced’, even if the incremental average annual treatment cost is not ‘high’.

As noted in the Conceptual Framework, the opportunity cost of adopting a new medicine is a function of its incremental cost compared to existing treatment. All else equal, the risk that adopting a new medicine will result in negative consumer surplus would therefore be expected to be greater for a medicine with high incremental average annual treatment cost, compared to a medicine with high absolute average annual treatment cost but low incremental average annual treatment cost. For this reason, the PMPRB may wish to consider ‘average annual treatment cost’ within Criterion D as being incremental upon existing treatment.

There are several considerations that would need to be made when calculating this incremental cost. The relevant treatment comparator would need to be established and the cost of treatment with the comparator estimated over the relevant time horizon. If the comparator is itself a patented medicine, then consideration would also need to be given to any expected reduction in the cost of the comparator should generic alternatives to the comparator become available during the patent life of the new medicine.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.4: The Working Group recommends that “average annual treatment cost” within Criterion D be considered as incremental upon existing treatment.

Members voted 11 in favour and 1 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.5 Relevant metrics

The Terms of Reference required that the Working Group examine and make recommendations regarding the “relevant metrics for selecting medicines that meet the identified criteria”. The chair interpreted this as referring to the measures and definitions used for each criteria. For example, if the term ‘substantial improvement’ is retained in Criterion A, how would ‘improvement’ be measured and how would a ‘substantial improvement’ be defined?

There was general agreement that the most appropriate metrics for each criterion would be those already used in Canadian practice. For example, if the PMPRB retains consideration of the ‘substantial improvement’ term in Criterion A, then the definition of ‘substantial improvement’ could be based upon the definition already adopted by the PMPRB. Other potential sources for definitions suggested by members included health technology assessment (HTA) and regulatory agencies in Canada.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.5: The Working Group recommends that the measures and definitions used for each criterion reflect existing Canadian practice.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.6 Determining a threshold for each criterion

In addition to identifying “relevant metrics”, the Terms of Reference required that the Working Group examine and make recommendations regarding “options” for using these metrics.

There was some discussion regarding how to determine an appropriate ‘threshold’ to adopt for each criterion, building upon some potential thresholds proposed by the PMPRB.

At the first meeting of the Working Group, the PMPRB proposed that, in considering Criterion B (‘The medicine’s opportunity cost exceeds its expected health gain’), the ICER could potentially be compared to a threshold of $30,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). This was based on an estimate by Ochalek et al. (2018) of the opportunity cost of funding new medicines within Canada’s public health care systems (considered further in Topic 2).1 Some members raised concern that a $30,000 per QALY threshold would be sufficiently low as to capture a substantial proportion of all new medicines considered by the PMPRB, such that categorization as ‘Category 1’ might not serve as a useful ‘screening’ mechanism. However, in light of the general consensus among the Working Group that Criterion B should not be considered by the PMPRB, no further discussion of this threshold took place.

The PMPRB also proposed a potential ‘market impact’ threshold of either $20m or $40m, and proposed that a medicine could be considered to be of ‘high market impact’ if it reached this threshold in any one of either the first 3 years or 5 years after launch. The PMPRB provided the Working Group with estimates of the proportion of all medicines that would be classified as ‘Category 1’ under each combination of these potential thresholds (based solely on Criterion C):

- $20m market size in any one of the first 3 years: 22% of all medicines

- $20m market size in any one of the first 5 years: 27% of all medicines

- $40m market size in any one of the first 3 years: 17% of all medicines

- $40m market size in any one of the first 5 years: 20% of all medicines

Finally, the PMPRB proposed a potential ‘average annual treatment cost’ threshold of $50,000. The PMPRB estimated that this threshold would result in 4% of all medicines being classified as ‘Category 1’ (based solely on Criterion D).

The Working Group noted that the sensitivity of each criterion as a ‘screen’ is dependent upon the threshold adopted. The Working Group did not have the necessary data to calculate how many medicines would be classified as ‘Category 1’ under different combinations of thresholds across the criteria. Furthermore, it was noted that the ‘ideal’ number of medicines to classify as ‘high risk’ depends upon the PMPRB’s capacity for assessing ‘Category 1’ medicines (which was unknown to the Working Group), while the ‘ideal’ types of medicines to classify as ‘high risk’ depend upon the policy intent.

The Working Group was therefore not in a position to make specific recommendations regarding the threshold to adopt for each criterion. Instead, the chair proposed that the PMPRB should determine the threshold for each criterion, taking into account its capacity for assessing ‘Category 1’ medicines, the technical considerations of the Working Group, and the policy intent.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.6: The Working Group recommends that a threshold for each criterion be determined by the PMPRB, taking into account its capacity for assessing ‘Category 1’ medicines, the technical considerations of the Working Group, and the policy intent.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.7 Clear specification of the threshold for each criterion

The two industry members on the Working Group emphasized the importance of the PMPRB clearly specifying the threshold to be used for each criterion, so as to provide a “clear bright line” to manufacturers.

A technical justification for this request is that a clear specification of the threshold for each criterion reduces uncertainty. The Conceptual Framework outlines how uncertainty in a medicine’s pharmacoeconomic value may result in an expected loss in economic surplus, such that there may be value in reducing this uncertainty. Similarly, uncertainty in whether a medicine may be subject to ‘Category 1’ classification may impose an expected loss on manufacturers and other stakeholders.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

1.7: The Working Group recommends that the threshold for each criterion be clearly specified, so as to reduce uncertainty for stakeholders.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

1.3.8 Other considerations

There was some discussion as to whether ‘high market impact’ should be considered as incremental upon existing treatment (similar to the consideration of ‘high average annual treatment cost’ in section 1.3.4). Some members argued that a medicine with high market size may replace an existing treatment which also has high market size, such that the net market impact is relatively small.

However, it was apparent from the PMPRB Guidelines Scoping Paper, as well as the proposed ‘market size adjustment’ (section 6), that there is a policy concern regarding medicines with high absolute market impact. The PMPRB confirmed to the chair that this was the case. Given this policy intent, the Working Group did not consider any potential recommendation to modify the wording of the ‘high market impact’ criterion so that it is incremental upon existing treatment.

2: Supply-side cost effectiveness thresholds

2.1 Terms of Reference

Within this area of focus, the Terms of Reference required the Working Group to examine and make recommendations with respect to the following considerations and questions:

Potential approaches for implementing a price ceiling based on a medicine’s opportunity cost.

Potential approaches for allowing price ceilings above opportunity cost for certain types of medicines (e.g. pediatric, rare, oncology, etc).

2.2 Policy Intent

The Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement includes the following statements which provide context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“Information regarding pharmacoeconomic value: patentees would be required to provide the PMPRB with all published cost-utility analyses that express the value in terms of the cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY). Cost-utility analyses are viewed by experts as the “gold standard” approach to considering the economic value of new medicines.”

(p.10, emphasis added)

“Without the proposed amendments, it is estimated that public health care systems from across Canada will spend an additional $3.9 billion (PV) for the same quantity of patented medicine. This represents a significant opportunity cost for the Canadian public health care system, as these funds could have been used in other areas of the health care system to better the health of Canadians.”

(p.16, emphasis added)

The PMPRB Guidelines Scoping Paper includes the following statement which provides context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“The first part of the test would assess the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of the drug, as determined by CADTH’s health technology assessment process, against an explicit cost effectiveness threshold. The threshold would be based on the opportunity cost associated with displacing the least cost effective health technology in the Canadian health system, otherwise understood as the marginal cost of a QALY, as calculated by expert health economists and revised periodically to reflect changing market conditions. Drugs that prolong life or provide significant QALY gains could be subject to a more generous threshold, as Canadian payers have demonstrated a higher willingness to pay for these types of drugs”.

(p.6, emphasis added)

The PMPRB Framework Modernization Presentation includes the following slide which provides context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

Part III: MRP for Category 1 drugs

Step 1: application of pharmacoeconomic factor

- Empirical work undertaken by Karl Claxton at the University of York suggests a $30K/QALY opportunity cost threshold for Canada.

- PMPRB will use this estimate at the screening phase to determine whether a drug should go in Category 1 or Category 2.

- Category 1 drugs will then be subject to a baseline maximum value-based price ceiling of $60K/QALY, for reasons of practicality and efficiency.

- Drugs that meet certain clinical characteristics (e.g., high burden of disease or significant absolute gain in QALY) may be subject to a higher $/QALY ceiling.

2.3 Summary of Deliberations

The Working Group’s deliberations on this topic were informed by two documents commissioned by the PMPRB prior to establishment of the Working Group:

- A white paper prepared by the Institute of Health Economics (IHE) titled “Theoretical models of the cost-effectiveness threshold, value assessment, and health care system sustainability”, hereafter referred to as the ‘IHE report’.2

- A report prepared by Jessica Ochalek and colleagues from the University of York titled “Assessing health opportunity costs for the Canadian health care systems”, hereafter referred to as ‘Ochalek et al. (2018)’.1

2.3.1 Appropriateness of using a supply-side threshold

As noted in the IHE report, a supply-side threshold can be used to estimate the ‘health opportunity cost’ associated with adopting a new medicine within a public health care system. This health opportunity cost is measured in units of health benefit (typically QALYs) and reflects the estimated health ‘forgone’ by other patients within the health care system if limited resources are used to adopt the new medicine.

For example, Ochalek et al. (2018) estimated a supply-side threshold of $30,000 per QALY for Canada as a whole, with some variation across provinces and territories (considered further in section 2.3.4). This estimate implies that every additional $30,000 spent on a new medicine results in one forgone QALY by other patients across Canada’s public health care systems. A higher estimate of the supply-side threshold would imply that fewer QALYs are displaced at any given incremental cost associated with a new medicine, and conversely a lower supply-side threshold would imply that more QALYs are displaced for any given incremental cost.

Additional explanation and examples are provided in the Conceptual Framework.

There was debate amongst Working Group members as to whether a supply-side threshold is always the most appropriate means for estimating the opportunity cost of new medicines. Specifically, consideration was given as to whether a ‘demand-side threshold’ might be more appropriate than a supply-side threshold in some cases.

As noted in the IHE report, a demand-side threshold reflects Canadians’ ‘willingness-to-pay’ for health benefits. Some members argued that a demand-side threshold might therefore be a more appropriate threshold for private insurers and patients who pay out-of-pocket.

Nevertheless, in light of the PMPRB’s clarification that the policy intent is to adopt the perspective of the Canadian public health care system (section 5.2), the focus of the Working Group’s deliberations was on a supply-side approach to estimating the threshold.

Since the policy intent is to adopt the perspective of Canada’s public health care systems, and since the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement views the QALY, as used in cost-utility analysis, as the “gold standard” approach to considering the economic value of new medicines, it follows that the most relevant measure of the opportunity cost of a new medicine, given this policy intent, is an estimate of the QALYs forgone by patients within Canada’s public health care systems. As noted in the Conceptual Framework, this may be estimated using an estimate of the incremental cost of the new medicine and an estimate of a supply-side cost-effective threshold, expressed in terms of cost per QALY.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.1: The Working Group regards the use of a supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold, as a means for estimating the opportunity cost of adopting new medicines within Canada’s public health care systems, as consistent with the policy intent.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.2 Uncertainty in the empirical evidence base

The Working Group was unanimous in considering the empirical evidence base with respect to Canadian estimates of supply-side thresholds to be uncertain.

The only existing estimate of a supply-side threshold for Canada is that provided by Ochalek et al. (2018). This work reported estimates of supply-side thresholds for each province and territory in terms of cost per disability adjusted life year (DALY) averted. Based on these estimates, the authors argued that “a cost per DALY threshold is likely to be less than $50,000 for Canada as a whole”. The authors further argued that “a cost per QALY threshold is likely to be similar or lower than a cost per DALY averted threshold”, concluding that “a cost per QALY threshold of $30,000 per QALY would be a reasonable assessment of the health effects of changes in health expenditure for Canada as a whole and is likely to be similar across most provinces”.

The authors acknowledged that this research was not primarily based upon Canadian data, noting that “further research to provide Canadian and/or province specific elasticity estimates using within country and within province data should be regarded as a priority”.

Some members of the Working Group expressed concerns with the instrumental variables (IVs) used by Ochalek et al. (2018).

One member noted that the authors employed two specific IVs that are potentially problematic:

- Military expenditure per capita of neighbouring countries;

- A measure of institutional quality, captured using:

- The level of infrastructure (proxied by ‘paved roads per square km’);

- Shock in ‘donor funding’ (absolute deviation from the historical mean).

This member viewed the appropriateness of these IVs as questionable in the Canadian context. Canada’s neighbor is the United States, which is an outlier in terms of military expenditure per capita in the sample of countries used in the Ochalek et al. (2018) study. Canada is also an outlier in terms of ‘paved roads per square km’, ranking 90th out of 125 countries.3 Since relatively few high income countries receive ‘donor funding’, this member noted that ‘paved roads per square km’ is effectively the sole IV for infrastructure quality.

These potentially ‘weak’ IVs raise concerns about the parameter estimates from the authors’ regression model. Specifically, if the IVs are only weakly correlated with the endogenous regressors, parameter estimates may be biased, estimates may be inconsistent, tests of significance may have incorrect size, and confidence intervals may be wrong.4–6

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.2: The Working Group regards the current evidence base with respect to Canadian estimates of supply-side cost-effectiveness thresholds, including the empirical research by Ochalek et al. (2018), as uncertain.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.3 Direction and magnitude of bias in the $30,000 per QALY estimate

Given the Working Group’s concern with the IVs used in the Ochalek et al. (2018) research, members considered the potential direction and magnitude of bias in the $30,000 per QALY estimate.

At a public seminar, the chair asked the corresponding author of the Ochalek et al. (2018) research, Dr Karl Claxton, for his views on the implications of any weakness in the IVs.7 Dr Claxton’s response was that any weakness in the IVs would be expected to weaken the relationship between health expenditures and health outcomes, in turn resulting in an overestimate of the cost-effectiveness threshold.

The implication of Dr Claxton’s remarks is that a re-estimate of the supply-side threshold with stronger IVs would be expected to be below $30,000 per QALY. However, the Working Group member who initially questioned the strength of the IVs in the Ochalek et al. (2018) research disagreed, arguing that the direction of bias as a result of weak IVs is unknown.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.3: The Working Group regards the direction and magnitude of any bias in the $30,000 per QALY estimate by Ochalek et al. (2018) to be unknown.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.4 Differences across provinces and territories

Several members noted that a different supply-side threshold would be expected for each Canadian public health care system.

Theoretically, the supply-side threshold is affected by the budget of the health care system in question, among other considerations.8 Since each provincial and territorial health care system has its own budget, a different supply-side threshold would be expected for each.

This is consistent with the results of the work by Ochalek et al. (2018), which found a different supply-side threshold (in terms of cost per DALY averted) in each province and territory.1

The Working Group considered several potential approaches for setting a single ceiling price across all provinces and territories, including:

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in the province or territory with the highest supply-side threshold;

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in the province or territory with the lowest supply-side threshold;

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective across Canada as a whole.

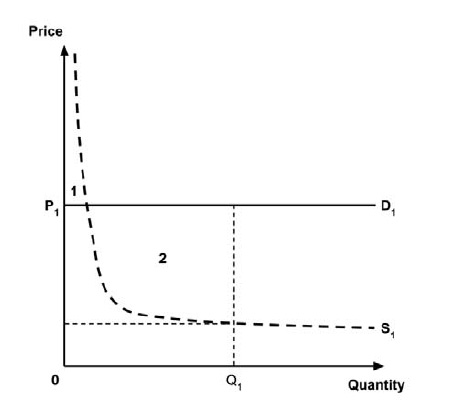

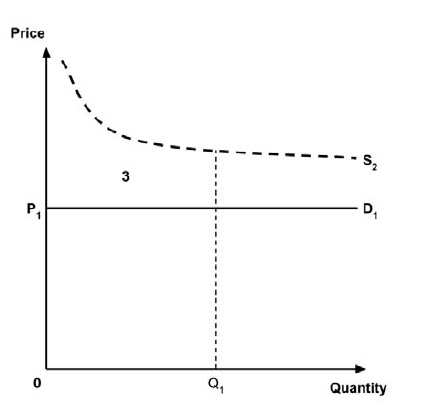

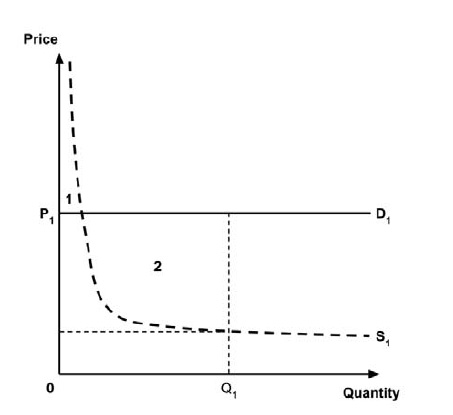

A consideration of the implications of each approach is provided in the Conceptual Framework. In summary, each approach results in a different allocation of the total ‘economic surplus’ among ‘consumers’ (patients) and ‘producers’ (manufacturers). The first approach results in negative overall consumer surplus, the second approach results in positive overall consumer surplus, while the third approach results in zero overall consumer surplus.

Since the preferred allocation of the economic surplus is a matter for policy makers, the Working Group does not advocate for any specific approach. Instead, the Working Group recommends that any single threshold used for the purpose of informing a ceiling price be consistent with the policy intent, given the technical considerations outlined by the Working Group.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.4: The Working Group recognizes that each provincial and territorial public health care system has a unique supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold, and recommends that any single threshold used for the purpose of informing a ceiling price be consistent with the policy intent.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.5 Medicines with large net budget impact

In theory, adopting medicines with a large net budget impact into a budget constrained public health care system would be expected to result in a disproportionately large opportunity cost.8,9 (Note that “net budget impact” is distinct from the “market size” consideration in section 6.)

One approach for dealing with this is to use a progressively lower supply-side threshold for medicines with progressively larger net budget impact. One member cited the empirical work by James Lomas, which estimated how the supply-side threshold for the English NHS would fall as the net budget impact of a new health technology increases.9 For new hepatitis C treatments, which had an estimated net budget impact of £772m in the first year of use, Lomas found that the supply-side threshold would need to be adjusted down from £12,936 per QALY (the supply-side threshold for marginal changes in health care expenditure) to £12,452 per QALY.9,10

The Working Group was unaware of any other attempts internationally to estimate supply-side thresholds associated with non-marginal changes in health expenditures. Since no equivalent empirical estimates are available for Canada, there is no data to inform such a downwards adjustment to the Canadian supply-side threshold at the present time.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.5: The Working Group recognizes that, in principle, a downwards adjustment should be applied to the supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold for medicines with substantial net budget impact, but notes that there is no Canadian empirical evidence to inform the magnitude of such an adjustment at the present time.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.6 Equity weights

The Terms of Reference tasked the Working Group with considering “Potential approaches for allowing price ceilings above opportunity cost for certain types of medicines (e.g. pediatric, rare, oncology, etc)”.

The Working Group noted that, under CADTH’s ‘reference case’ requirements, all QALYs are assigned equal value. A justification of this position is provided in CADTH’s ‘Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada’ (4th Edition; pp.59-60).11 CADTH’s reference case therefore reflects an equity position under which a ‘weight’ of 1 is applied to all QALYs, regardless of any characteristics of the patients, disease or technology in question.

Critically, a weight of 1 on all QALYs does not permit a ceiling price “above opportunity cost” for “certain types of medicines” but not others. The Working Group therefore considered the potential for applying different weights to some QALYs, and hence departing from CADTH’s reference case assumption that all QALYs have equal value.

There is a small but growing empirical literature on the types of characteristics for which society may assign greater or lesser weight when valuing health gains.12–18 One member provided the Working Group with a brief summary of this literature. Characteristics that are often found to be important in empirical studies include severity of illness (particularly the presence or otherwise of life threatening or progressively chronically debilitating illness), the availability of active treatment alternatives, the prevalence of disease, the type of health gain (such as a reduction in pain), and the magnitude of health gain. These factors are often found to interact with one another, and so should not be considered independently. In the opinion of this member, greater empirical work is needed to fully understand these interactions and the ‘weights’ that would be put on each characteristic.

Members also discussed theoretical issues associated with applying weights to some QALYs but not others. One member expressed concern that some important conceptual problems have not yet been addressed in the literature - for example, would a greater weight on QALYs for ‘cancer’ apply to all QALYs gained by a patient with cancer (including those gained through treatment for other diseases) or only the QALYs gained through cancer treatment (such that other QALY gains for the same patient for other diseases would be assigned different weight). There is also an ongoing and unresolved debate regarding whether weights should be applied directly to QALYs or to the cost-effectiveness threshold. The latter approach has been used by NICE in the UK but has received criticism for resulting in ‘inconsistencies’ in its consideration of social value.19

As a result of these limitations in the empirical and theoretical literature, the predominant view of members was that equity weights other than 1 should not be implemented at the present time.

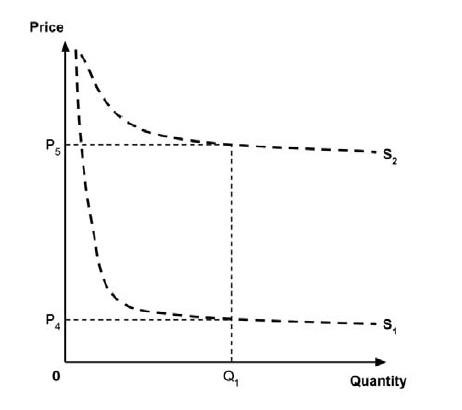

There was some discussion by the Working Group regarding the potential implications of this recommendation for medicines for rare diseases. As noted in the Conceptual Framework, medicines with small market size may be expected to have a higher supply curve (at the respective quantity) than medicines with large market size. Such medicines may therefore be less profitable at a given ceiling price compared to medicines with larger market size. This issue is considered further in section 6.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.6: The Working Group does not recommend the implementation of ‘equity weights’ other than 1, as would be required to allow price ceilings above opportunity cost for some medicines but not others, due to limitations in the existing theoretical and empirical evidence base.

Members voted 9 in favour and 3 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.7 Clear specification of the supply-side threshold

In common with the request that any thresholds used for classifying ‘Category 1’ medicines be clearly specified (section 1.3.7), the two industry members emphasized the desirability that any supply-side threshold used for the purposes of informing a price ceiling be clearly specified.

As noted in the Conceptual Framework, the supply-side threshold is a key determinant of the location of the ‘demand curve’ for a new medicine. A technical justification for requesting that the supply-side threshold be clearly specified is that it reduces uncertainty for manufacturers regarding the location of this demand curve, and hence the producer surplus if the ceiling price is informed by this demand curve.

There was general agreement among the Working Group about the desirability of specifying the supply-side threshold, and hence providing greater clarity to manufacturers and other stakeholders regarding the location of the demand curve.

Nevertheless, as noted in the Conceptual Framework, there is also considerable uncertainty about the location of the manufacturer’s ‘supply curve’. This increases uncertainty regarding the set of possible ceiling prices at which consumer and producer surplus are both positive, potentially resulting in a loss of economic surplus for both consumers and producers. To minimize this uncertainty, efforts should be made to better understand the location of the supply curve for new medicines. This would complement efforts to provide greater certainty regarding the location of the demand curve through a clear specification of the supply-side threshold.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.7: The Working Group recommends that any estimate of the supply-side threshold adopted by the PMPRB for the purposes of informing a price ceiling be clearly specified, so as to reduce uncertainty for stakeholders.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.8 Further empirical research

Given the uncertainties in the existing empirical evidence base regarding Canadian supply-side cost-effectiveness thresholds (sections 2.3.2 and 2.3.3), there was broad support among members of the Working Group for conducting further empirical research.

Since differences in supply-side thresholds across provinces and territories are predicted by theoretical work and were observed by Ochalek et al. (2018) (section 2.3.4), there was also agreement that any future Canadian empirical studies should consider potential variation in estimates of supply-side cost-effectiveness thresholds across jurisdictions within Canada.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.8: The Working Group recommends that the PMPRB support further empirical research to estimate a supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold for Canada. This research should consider and report on variation in estimates of supply-side cost-effectiveness thresholds across jurisdictions within Canada.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

2.3.9 Specifying an ‘interim’ threshold

Since the existing empirical evidence on Canadian supply-side thresholds was considered to be uncertain, and since further empirical research will take time to conduct and report, members discussed how a threshold might be specified by the PMPRB in the interim.

Existing Canadian policy thresholds

One potential interim approach considered by the Working Group is for the PMPRB to specify a threshold in line with existing ‘policy thresholds’ used by Canadian HTA agencies.

The Working Group observed that no Canadian HTA agencies currently specify an explicit cost per QALY policy threshold. However, one member noted that INESSS uses an informal policy threshold of $50,000 to $100,000 per QALY, with other members providing anecdotal evidence of similar policy thresholds being used informally by other HTA agencies in Canada (with higher policy thresholds used in some cases, such as for cancer).

Another member suggested that it may be useful to understand what policy threshold is informally used by the the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA) in its negotiations.

One member cited a 2016 article in the Hamilton Spectator, which reported that “the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review has set an unofficial threshold of $100,000 per quality-adjusted life year for new cancer medications”, and also a 2009 letter by the Deputy Minister of Health and Long-Term Care for Ontario, which noted that the Committee to Evaluate Drugs “typically considers a range of $40-60,000 [per] QALY as an acceptable range”.20,21

Taken together, this evidence suggests that informal policy thresholds used by HTA agencies in Canada are in the region of $50,000 to $100,000 per QALY, with oncology medicines assessed at the higher end of this range and other medicines assessed relatively lower within this range.

It should be noted that none of these policy thresholds is based on an empirical assessment of the opportunity cost of adopting new medicines within Canada’s public health care systems, as would be required to specify a ‘supply-side’ threshold.

Supply-side thresholds from other jurisdictions

Another potential interim approach is to consider empirical estimates of supply-side thresholds for other jurisdictions with similar wealth and medicine market characteristics as Canada.

The IHE report summarized three existing published estimates of supply-side thresholds for other jurisdictions:2

- The work by Claxton et al. (2015), which estimated a supply-side threshold of

£12,936 per QALY for the public health care system in the UK.10

- The work by Vallejo-Torres et al. (2017), which estimated a supply-side threshold of between €21,000 and €25,000 per QALY for the public health care system in Spain.22

- The work by Edney et al. (2017), which estimated a supply-side threshold of

AU$28,033 per QALY for the public health care system in Australia.23

The chair noted that the $30,000 per QALY estimate from Ochalek et al. (2018) is broadly in line with these estimates, and that all three of these countries are on the proposed PMPRB12 list of countries with “reasonably comparable economic wealth” and “similar medicine market size characteristics” as Canada. Absent reasons why Canada would be considered an ‘outlier’ among PMPRB12 countries, one might therefore reasonably expect a future Canadian estimate of a supply-side threshold to be similar to the estimates reported in these countries. Nevertheless, given the various determinants of the supply-side threshold, some variation in estimates across countries would be expected.8

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

2.9: The Working Group recommends that any ‘interim’ threshold specified by the PMPRB prior to completion of further Canadian empirical work should be informed by a comprehensive consideration of existing thresholds used by Canadian HTA agencies and empirical estimates of supply-side thresholds from other relevant jurisdictions.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

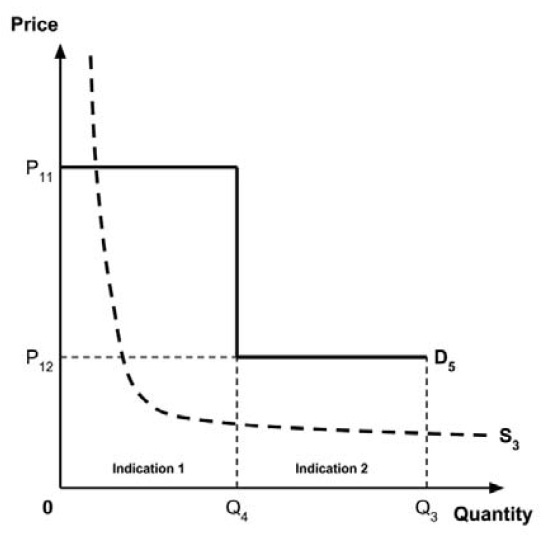

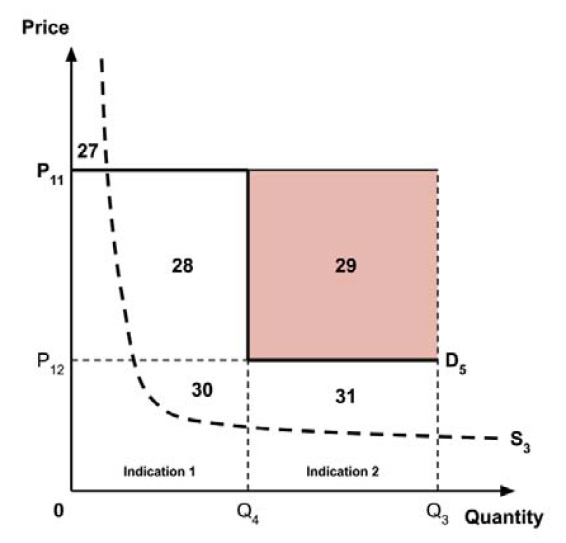

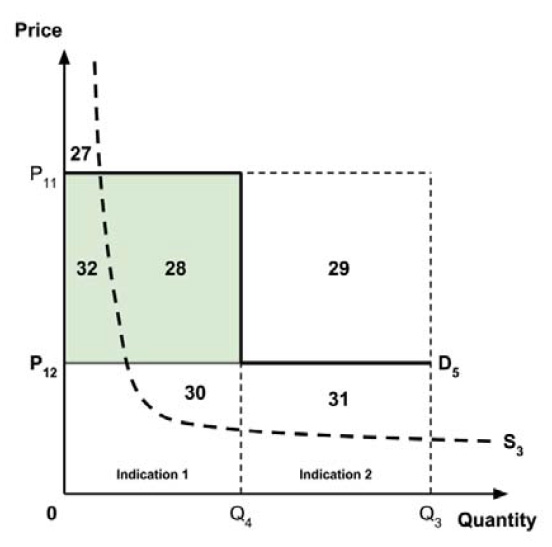

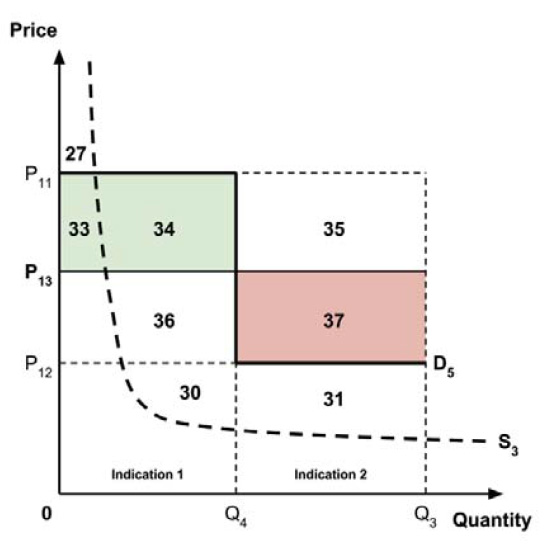

3: Multiple indications

3.1 Terms of Reference

Within this area of focus, the Terms of Reference required the Working Group to examine and make recommendations with respect to the following considerations and questions:

Options for addressing medicines with multiple indications (e.g. multiple price ceilings or a single ceiling reflecting one particular indication).

3.2 Policy Intent

The Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement includes the following statements which provide context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“The price paid for a medicine should take into consideration the value it produces.”

(p.8, emphasis added)

The PMPRB Guidelines Scoping Paper includes the following statement which provides context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“The fifth and final part of the new framework would involve the periodic “re-benching” of drugs to ensure that previous determinations of potential excessive pricing and/or price ceilings remain relevant in light of new indications (resulting in a change of market size) or changes in market conditions. Depending on the nature of the change, the re-benching process could result in a decrease or increase in ceiling price.”

(p.7, emphasis added)

3.3 Summary of Deliberations

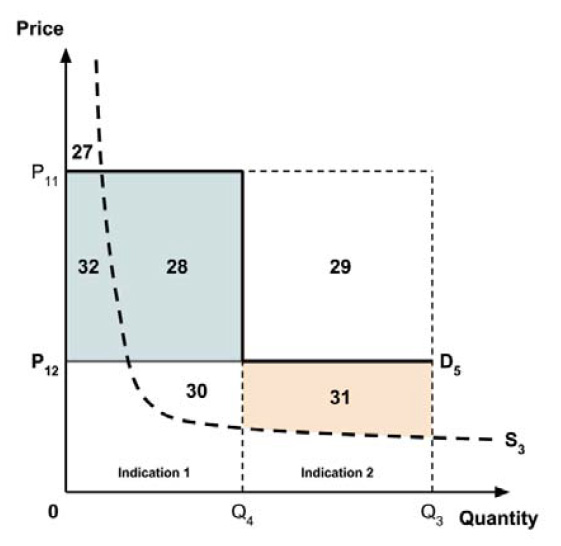

Two broad approaches were considered by the Working Group: a separate ceiling price for each indication (‘indication-specific pricing’), or a single ceiling price across all indications.

There was general agreement that indication-specific pricing is the more appealing approach in principle. As noted in the Conceptual Framework, the incremental effectiveness of any medicine generally differs across indications. Indication-specific pricing would permit the ceiling price of the medicine to reflect this differing value for each indication. This would appear to closely align with the policy intent, as stated in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement, that “the price paid for a medicine should take into consideration the value it produces”.

However, although one member was of the view that multi-indication pricing may be feasible for some ‘Category 1’ medicines, several members expressed concern that indication-specific pricing is not possible in Canada, given current limitations in data capture and reporting.

It was noted that indication-specific pricing requires an IT infrastructure for collecting data on volume per indication. An informal review conducted by one member identified a number of different approaches internationally.24,25 France, Germany and Australia all use indication-specific pricing, based on expected patient volumes for each indication. Italy engages in risk-sharing arrangements using indication-specific patient registries. Express Scripts in the United States is using indication-specific pricing for cancer medicines, and the UK piloted the feasibility of this approach using the Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy Dataset (SACT) data set. Belgium and Spain have also used indication-specific pricing for expensive medicines and hospital-based medicines, respectively.

Since logistical and implementation issues were out of the scope of the Terms of Reference, Working Group members did not give detailed consideration to the feasibility of implementing indication-specific pricing in Canada. Instead, the Working Group’s deliberations focused exclusively on options for specifying a single ceiling price across multiple indications.

3.3.1 Specifying a single ceiling price across all indications

The Working Group considered several potential approaches for setting a single ceiling price across multiple indications, including:

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in the most cost-effective indication;

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in the least cost-effective indication;

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective across all indications;

- A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in the first indication considered by the PMPRB.

A consideration of the implications of each approach is provided in the Conceptual Framework.

In common with the different potential approaches for setting a ceiling price across provinces and territories (section 2.3.4), each approach results in a different allocation of the total economic surplus among consumers and producers. The first approach results in negative overall consumer surplus, the second approach results in positive overall consumer surplus, the third approach results in zero overall consumer surplus, while the fourth approach results in zero expected consumer surplus if manufacturers do not behave strategically when launching medicines or negative expected consumer surplus if manufacturers do behave strategically.

At the final in-person meeting, the PMPRB asked the chair to consider a fifth potential approach for setting a single ceiling price across multiple indications:

- 5. A ceiling price at which the medicine is ‘just’ cost-effective in one specific ‘key’ indication identified by the PMPRB.

This approach has similarities to the fourth approach considered above, insofar as the ceiling price would be based upon the cost-effectiveness of the new medicine in one indication only. It would also share an advantage that the fourth approach has over the first three approaches, insofar as the ceiling price would not need to be rebenched over time as new indications are launched (unless the ‘key’ indication were to change).

The implications for the allocation of the total economic surplus with this fifth approach depend upon whether the ‘key’ indication is more or less cost-effective than other indications. If this ‘key’ indication is the most cost-effective, then the implications are the same as for the first approach, with negative overall consumer surplus. Alternatively, if the ‘key’ indication is the least cost-effective, then the implications are the same as for the second approach, with positive overall consumer surplus. In both cases consumer surplus in the ‘key’ indication is zero.

As with the consideration of different potential approaches for setting a ceiling prices across provinces and territories (section 2.3.4), the Working Group does not advocate for any specific approach since the preferred allocation of the economic surplus is a matter for policy makers.

Instead, the Working Group recommends that any single threshold used for the purpose of informing a ceiling price be consistent with the policy intent, given the technical considerations outlined by the Working Group.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

3.1: The Working Group recommends that the PMPRB specify a single ceiling price for each medicine that applies across all indications and is consistent with the policy intent.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

4: Accounting for uncertainty

4.1 Terms of Reference

Within this area of focus, the Terms of Reference required the Working Group to examine and make recommendations with respect to the following considerations and questions:

Options for using the CADTH and/or INESSS reference case analyses to set a ceiling price.

Options for accounting for and/or addressing uncertainty in the point estimate for each value-based price ceiling.

4.2 Policy Intent

The Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement includes the following statements which provide context regarding the policy intent with respect to this area of focus:

“In recognition of the significant expertise that can be necessary to prepare and validate cost-utility analyses, reporting would be limited to those that have been prepared by a publicly funded Canadian organization, such as the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) or the Institut national d’excellence en santé et services sociaux (INESSS). These organizations have dedicated expertise, and they generally conduct pharmacoeconomic analyses for medicines seeking to be reimbursed by public insurers. The PMPRB would consider these analyses in its evaluation of price excessiveness. It would not duplicate the work conducted by CADTH and INESSS as part of reimbursement processes.”

(pp.10-11, emphasis added)

None of the documents provided to the Working Group by the PMPRB included any statement regarding the policy intent with respect to “options for accounting for and/or addressing uncertainty in the point estimate for each value-based price ceiling”.

4.3 Summary of Deliberations

4.3.1 Using the CADTH and/or INESSS reference case analyses

The Terms of Reference tasked the Working Group with considering “options for using the CADTH and/or INESSS reference case analyses to set a ceiling price”.

Members discussed how the results of pharmacoeconomic analyses of a medicine reported by CADTH, INESSS and other Canadian HTA agencies generally differ from those reported by the manufacturer and also from each other. The industry members argued that cost-utility estimates by CADTH and INESSS “often exhibit differences in their estimates pertaining to heterogeneous assumptions and expert opinions”, and that this variability is “a function of the analyst that produces the assessment and the peer reviewers that challenge the analyses”.

Members also discussed whether the assumptions adopted by CADTH and INESSS in their ‘reference case’ analyses are appropriate for use by the PMPRB when setting ceiling prices. Some members suggested that the PMPRB might wish to establish its own ‘reference case’, clearly specifying the requirements and any necessary assumptions for pharmacoeconomic analyses used to inform ceiling prices. Although the policy intent is to “not duplicate the work conducted by CADTH and INESSS”, possible departures from existing CADTH and INESSS reference case assumptions include a clear specification of a supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold and a potential departure from the assumption of risk-neutrality (see section 4.3.3).

Since matters of process were beyond the remit given by the Terms of Reference, the Working Group did not consider what specific processes might be established by the PMPRB to arrive at a single set of pharmacoeconomic results from which to inform a ceiling price. Nevertheless, there was a widespread view among Working Group members that clarity is required in whatever processes are established by the PMPRB.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

4.1: The Working Group recognizes that there is variation in the results of pharmacoeconomic analyses reported by CADTH and INESSS, and recommends that the PMPRB establish clear processes for identifying how these analyses will be used to inform a ceiling price.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

4.3.1 Ensuring unbiased estimates

The Working Group noted that the most recent edition of CADTH’s ‘Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada’ (4th Edition) includes specific recommendations for addressing uncertainty in pharmacoeconomic analysis.11 These include an assessment of parameter uncertainty (through probabilistic analysis), structural uncertainty (through scenario analysis), and methodological uncertainty (through a comparison of ‘reference case’ and ‘non-reference case’ analyses). INESSS has similar requirements for considering uncertainty.26

Some members expressed concern that not all pharmacoeconomic analyses currently satisfy these recent CADTH guidelines, and that better enforcement of these guidelines is needed to ensure that uncertainty is appropriately addressed in all pharmacoeconomic analyses considered by the PMPRB when informing ceiling prices.

Members also noted that current HTA processes at CADTH and INESSS are undertaken for the purpose of assisting public payers in making decisions related to funding and informing pricing negotiations, rather than to inform ceiling prices set by the PMPRB. There was broad agreement that the PMPRB should engage with CADTH and INESSS, and any other relevant stakeholders, regarding modifications that may be required to these processes given the proposed change in the context of their use.

While considerations of the specific processes adopted by CADTH and INESSS are beyond the scope of the Working Group, the key technical principle is that all pharmacoeconomic analyses should satisfy the same basic set of requirements, including a comprehensive and unbiased assessment of parameter uncertainty, structural uncertainty and methodological uncertainty.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

4.2: The Working Group recommends that all pharmacoeconomic analyses used for the purpose of informing a ceiling price should satisfy the requirements of the most recent edition of CADTH’s ‘Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada’, including an unbiased assessment of parameter uncertainty, structural uncertainty and methodological uncertainty.

Members voted 12 in favour and 0 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

4.3.2 Addressing uncertainty in the point estimate

The Terms of Reference also required the Working Group to consider “options for accounting for and/or addressing uncertainty in the point estimate for each value-based price ceiling”.

It was agreed that there are a number of sources of uncertainty in any pharmacoeconomic analysis. One member noted that clinical uncertainty is typically the primary source of uncertainty when CADTH considers new medicines, particularly for rare conditions. There are also uncertainties in the incremental costs associated with new medicines.

Furthermore, since the supply-side threshold requires empirical estimation, it will inevitably be uncertain. For example, the UK research which estimated a supply-side threshold reported a probability distribution in addition to a point estimate.10

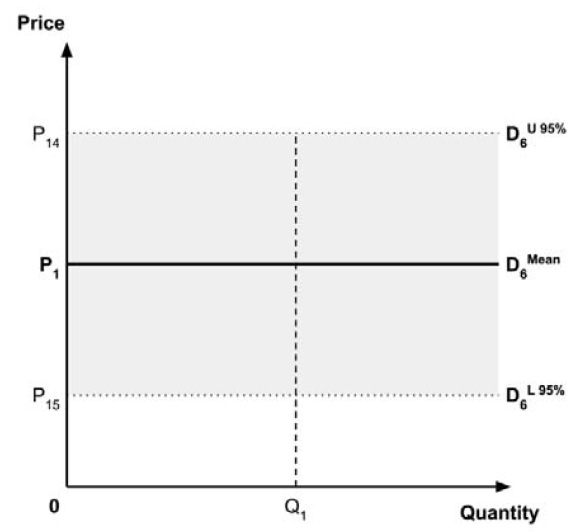

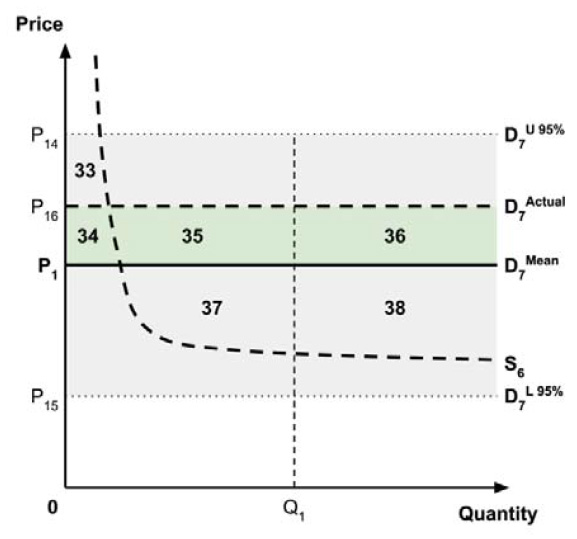

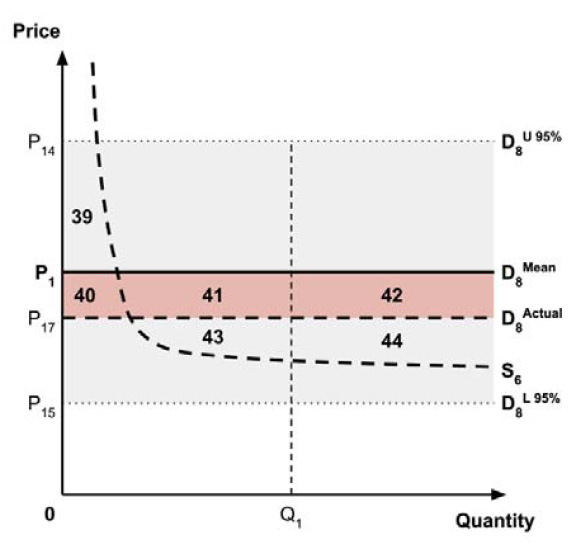

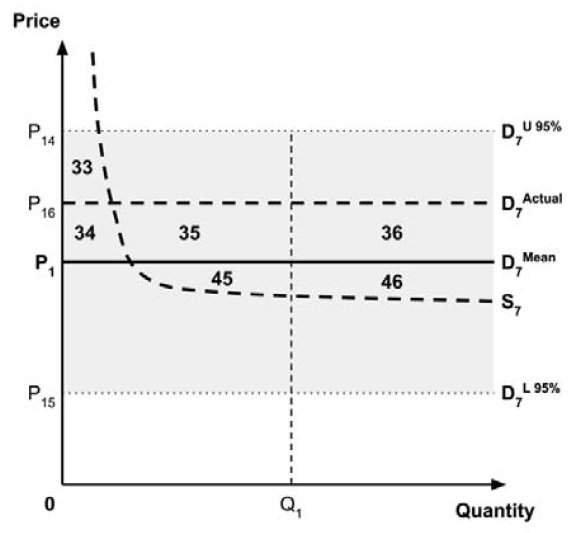

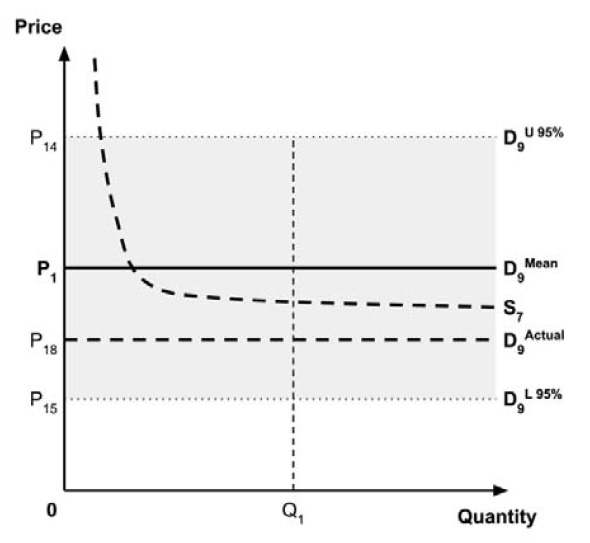

As noted in the Conceptual Framework, any uncertainty in the incremental costs and benefits results in uncertainty in the ICER. The price at which the ICER is equal to the supply-side threshold is also uncertain, resulting in uncertainty in the true location of the demand curve. This, in turn, results in uncertainty in the ceiling price that is consistent with the policy objective regarding the allocation of the economic surplus between consumers and producers.

Some members noted that CADTH does not always report a point estimate for the ICER, but that a point estimate would be required for the purposes of informing a ceiling price.

Members discussed how a ceiling price might be informed when there is uncertainty around the ICER. The standard approach for considering uncertainty in economic evaluations is to use the expected values of the incremental costs and incremental benefits in order to calculate an ICER. This is the approach adopted in CADTH’s ‘Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada’ (4th Edition).11 This approach implicitly assumes ‘risk neutrality’, which is typically justified on the basis of the Arrow-Lind principle.27

Members also debated using the upper bound of the credible interval around the ICER. Concern was raised that this approach would provide a disincentive for manufacturers to conduct research that reduces uncertainty around the ICER, since additional uncertainty would be rewarded with a higher ceiling price. It would also result in negative expected consumer surplus.

As noted in the Conceptual Framework, if the standard approach is adopted and a ceiling price is specified at which the ICER (calculated by dividing the expected incremental costs by the expected incremental QALYs) equals the expected value of the supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold, then the expected consumer surplus would be zero. (Note that the actual consumer surplus may be positive or negative, but the expected consumer surplus would be zero).

If the policy intent is to ensure that expected consumer surplus is non-negative, and if a risk-neutral position is adopted, then this would be the highest ceiling price consistent with this policy objective. Alternatively, if a risk-adverse position is adopted, then a higher or lower ceiling price is required to mitigate this risk. Raising the ceiling price may reduce the risk that a medicine is not launched, while lowering the ceiling price may reduce the risk that a medicine results in negative consumer surplus.

Since the PMPRB’s risk attitude is not known, the Working Group cannot specify the most appropriate option for informing a ceiling price. Instead, the Working Group recommends that the PMPRB adopt an approach for considering uncertainty that is consistent with its risk attitude. If the PMPRB is ‘risk-neutral’, this requires that the ceiling price be informed by the expected values of the incremental costs and QALYs for the medicine and the expected value of the supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold. If the PMPRB is not ‘risk-neutral’, then consideration should be given to setting a ceiling price that is higher or lower than that under risk neutrality, given the policy intent.

The following potential recommendation was put to a vote of the Working Group:

4.3: The Working Group recommends that the PMPRB adopt an approach for considering uncertainty that is consistent with its risk attitude. If the PMPRB is ‘risk-neutral’, this requires that the ceiling price be informed by the expected values of the incremental costs and QALYs for the medicine and the expected value of the supply-side cost-effectiveness threshold. If the PMPRB is not ‘risk-neutral’, then consideration should be given to setting a ceiling price that is higher or lower than that under risk neutrality, given the policy intent.

Members voted 10 in favour and 2 against this potential recommendation.

This was therefore adopted as a formal recommendation of the Working Group.

4.3.3 Value of information analysis

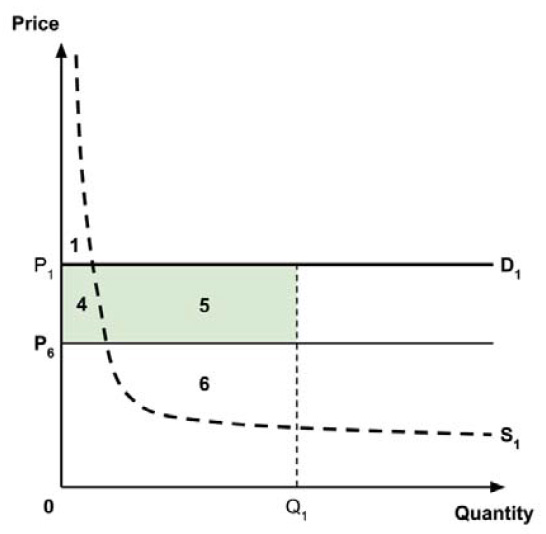

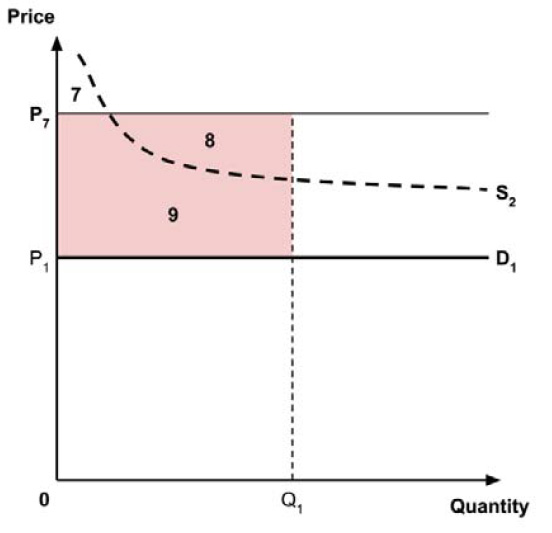

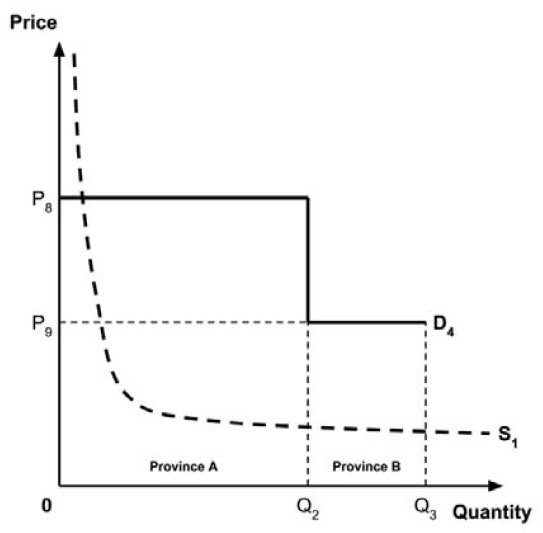

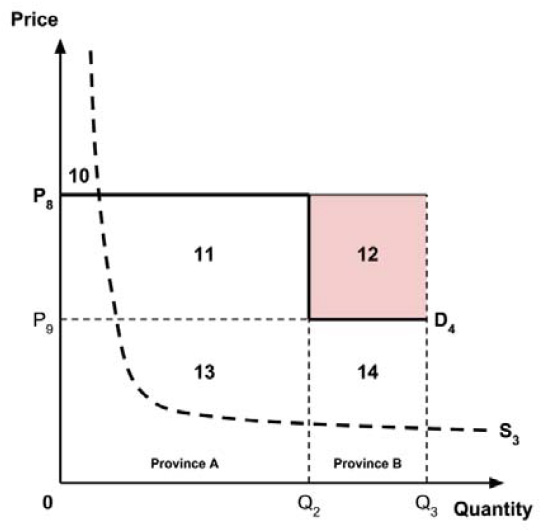

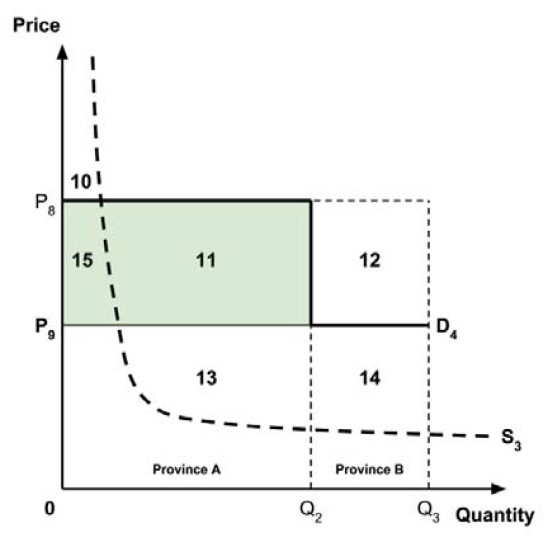

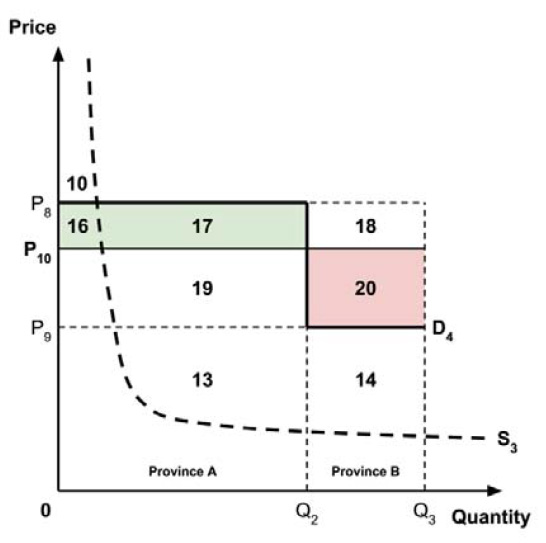

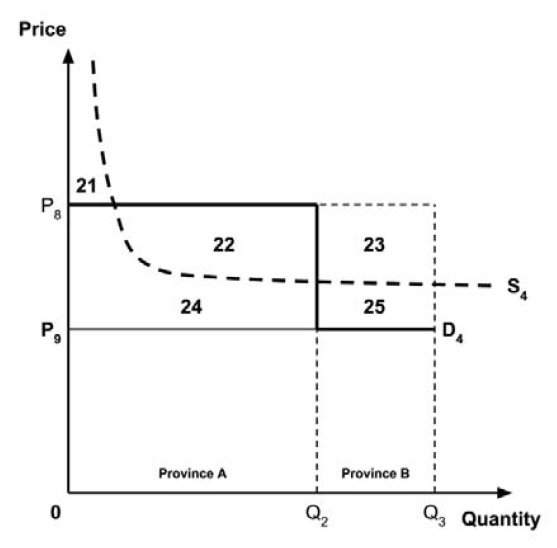

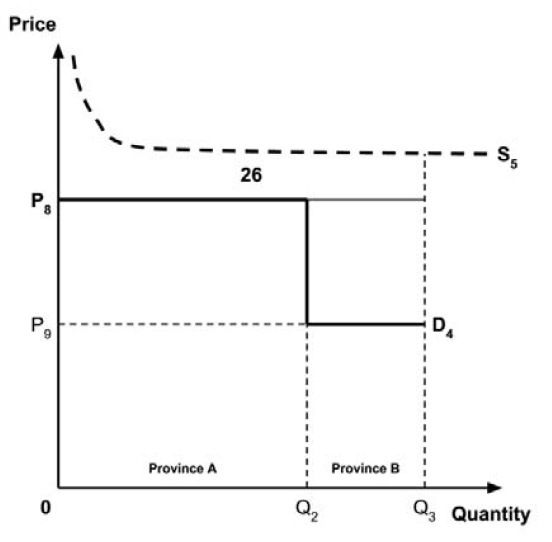

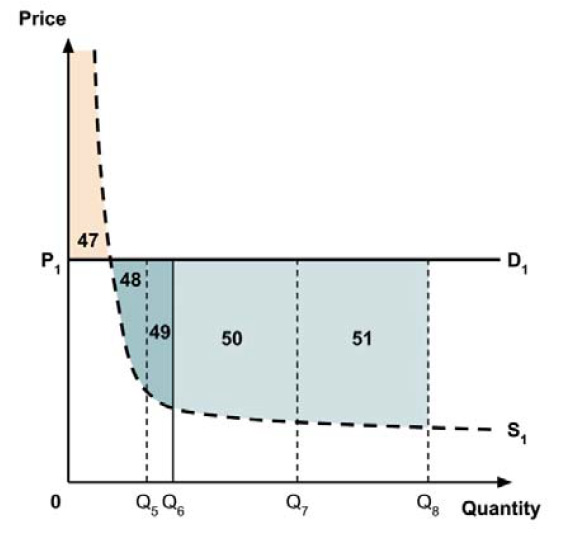

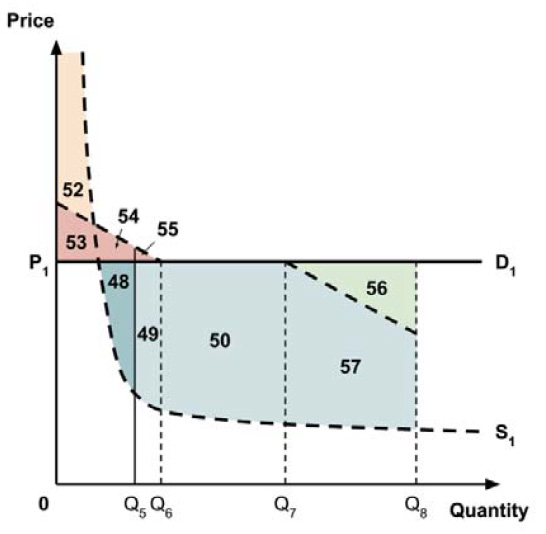

In conventional pharmacoeconomics, the expected loss in consumer surplus that results from uncertainty is estimated using ‘value of information’ (VOI) analysis.