Private Drug Plans in Canada - Part 1: Generic Market 2005–2013

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) as part of the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS).

The PMPRB would like to acknowledge the contributions of:

- The members of the NPDUIS Advisory Committee, for their expert oversight and guidance in the preparation of this report.

- The PMPRB NPDUIS staff for their contribution to the analytical content of the report:

- Tanya Potashnik – Director, Policy and Economic Analysis

- Elena Lungu – Manager, NPDUIS

- Carol McKinley – Communication Advisor

- The PMPRB scientific and editing groups

Disclaimer

NPDUIS is a research initiative that operates independently of the regulatory activities of the Board of the PMPRB. The statements and opinions expressed in this NPDUIS report do not represent the position of the PMPRB with respect to any regulatory matter.

Parts of this material are based on data and information provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. However, the analyses, conclusions and/or statements expressed herein are not those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Although based in part on data obtained under license from the IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database and IMS AG’s MIDAS™ Database, the statements, findings, conclusions, views and opinions expressed in this report are exclusively those of the PMPRB and are not attributable to either IMS Brogan or IMS AG.

Contact Information

Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

Standard Life Centre

Box L40

333 Laurier Avenue West

Suite 1400

Ottawa, ON K1P 1C1

Telephone: 1-877-861-2350

TTY: 613-288-9654

Email: PMPRB.Information-Renseignements.CEPMB@pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca

Executive Summary

Significant developments in the generic drug market have recently shaped the drug expenditure landscape in Canada. Many blockbuster brand-name drugs have lost patent protection and are now facing generic competition. In addition, most provincial governments have implemented generic pricing policies that have reduced the price of generic drugs in Canada. Both trends have undoubtedly resulted in important cost savings and have slowed the growth of drug expenditures in Canada.

This report focuses on these trends from the perspective of Canadian private drug plans, providing insight into the evolving generic market shares and the reimbursed unit costs, as well as dispensing patterns and their impact on overall prescription costs. A comparative analysis with Canadian public drug plans and select international markets is also included in the study. The reporting focuses on the 2013 calendar year, with a retrospective look at the trends since 2005.

This is the first of three reports in a PMPRB series that analyzes trends in Canadian private drug plans. The other two reports focus on cost drivers and high-cost drugs. The series provides policy makers and researchers with insights into relevant trends, sources of cost pressures, and possible areas for cost-saving opportunities. Private insurance is the second largest market for prescribed drugs in Canada, accounting for an estimated 34.5% ($10.1 billion) of prescribed drug spending in 2013 (CIHI 2014).

Previous PMPRB reports analyzed the generic market and drug plans in Canada from various perspectives. A recent report examined the reduction in generic prices, and concluded that Canadian generic drug price levels in 2013 continued to be higher than those of other industrialized countries (PMPRB 2014). Another study analyzed the cost drivers in public drug plans and found that generic substitution and price reductions exerted an important pull-down effect on drug costs in public drug plans in 2012/13 (PMPRB 2015).

The main data source for this report was the IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database. The results for private plans were compared with a select number of public drug plans in the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information. The IMS AG MIDAS™ Database was used for the international market analysis.

Key Findings

Despite significant differences in plan design and beneficiary populations, the use and cost of generic drugs in most private plans were similar to those in public plans in 2013. Private plans in Quebec were a notable exception, with lower generic market shares and higher prescription costs compared to other private and public plans. The frequency of dispensing was a key factor in driving differences in the prescription costs for generic drugs, especially in private plans in Quebec, where it resulted in higher costs being reimbursed for the dispensing of any given quantity of drugs. Most other private plans had a lower dispensing frequency than their corresponding public plans, resulting in lower prescription costs for generics.

Canada had one of the highest generic market shares in 2013.

Compared to the other seven industrialized countries that the PMPRB considers in reviewing the prices of patented drug products, Canada had the third highest generic market share in terms of drug volume (70%) after Germany (72%) and the US (78%).

The generic market share in private plans increased in recent years, but continued to be lower than in public plans.

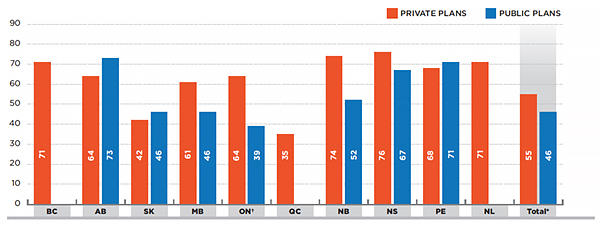

The generic share of prescriptions in private plans has increased markedly in recent years, from 37% in 2005 to 55% in 2013. Despite this increase, the share remained lower than in public plans, which was 71% in 2013.

The differences in generic market shares in private and public plans reflected the demographic and disease profiles of the populations.

There are differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the beneficiary populations in private and public plans which explain, for the most part, the differences in generic market shares. However, at drug level, the generic market share in most private plans closely mirrors those in corresponding public plans. A complete alignment of the use of generics between private and public plans would only result in marginal increases in private generic market shares and any related cost-savings.

Limiting the reimbursement of brand-name drugs to the generic price level would have resulted in important cost savings in all private plans.

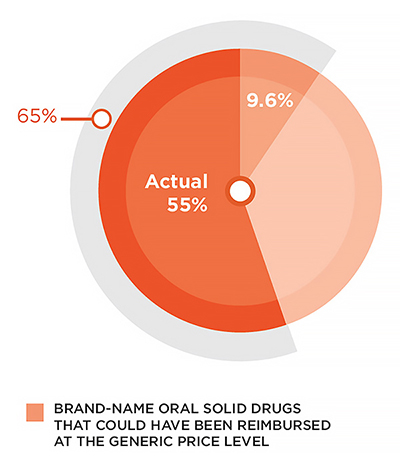

In 2013, if the private plans had limited the reimbursement of brand-name drugs in oral solid form to the generic price level, up to 9.6% of prescriptions would have been impacted. This would have increased the share of prescriptions reimbursed at the generic price level to 65%, resulting in an estimated reduction of up to 5.7% in retail drug costs.

Generic Share of Prescriptions in Private Plans, 2013

Figure description

This pie graph illustrates the share of generic prescriptions for oral solid drugs in Canadian private plans. In 2013, generic drugs represented 55% of all prescriptions. An additional 9.6% of prescriptions were for brand-name drugs with available generic equivalents. If these drugs had been reimbursed at the generic price level, this would have brought the total generic share to 65%.

Note: Estimated results are restricted to oral solid drugs with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database.

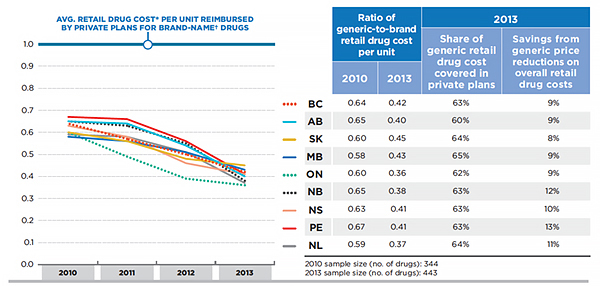

Provincial generic pricing policies resulted in significant cost savings for private plans.

Generic pricing policies introduced by most provincial governments markedly reduced the prices of generic drugs reimbursed by private plans from an average of 63% of the brand-reference in 2010 to 42% in 2013. These reductions resulted in important cost savings for private plans, ranging from 8% to 13% of the overall retail drug cost in 2013, depending on the province.

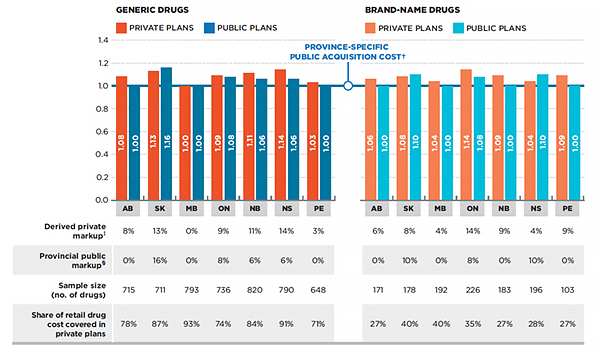

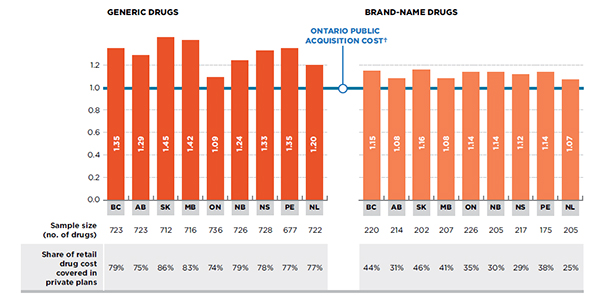

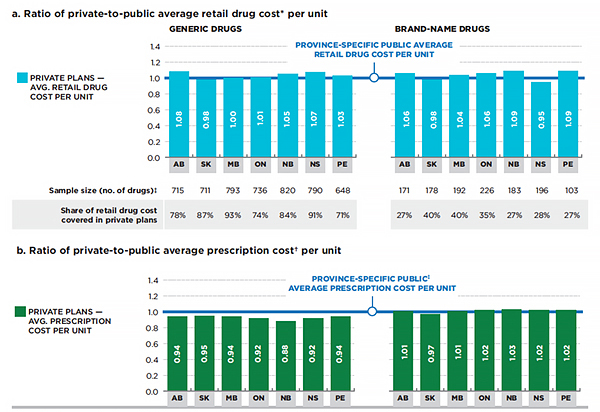

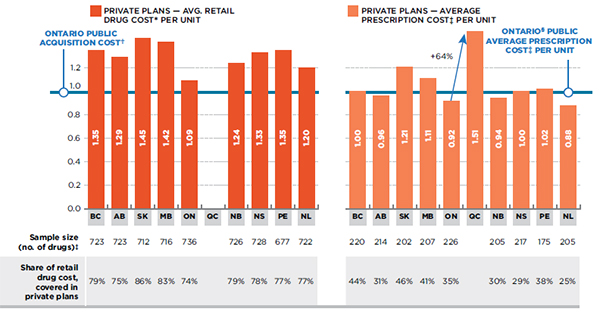

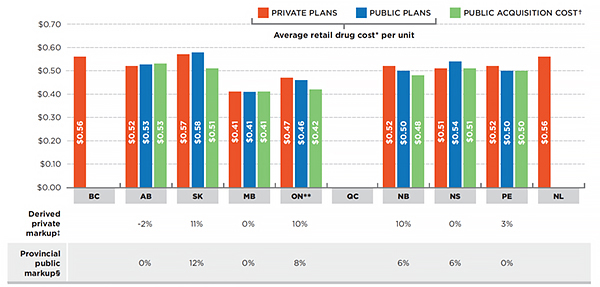

Public and private plans reimburse approximately the same retail drug cost for generic drugs.

At a provincial level, private and public plans reimbursed comparable average retail drug costs per unit for generic drugs. Private plans in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Alberta were notable exceptions, with higher retail unit cost levels (5% to 8%), suggesting higher markups than in the corresponding public plans. Interprovincial variations in 2013 resulted from the evolving provincial generic pricing policies.

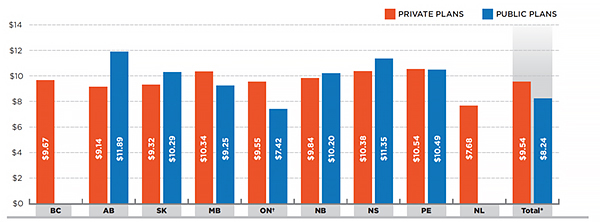

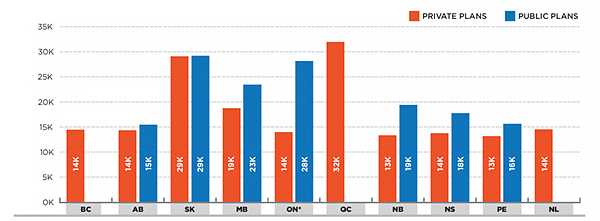

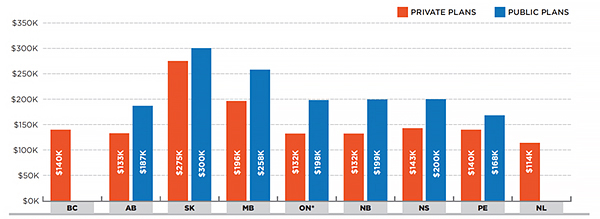

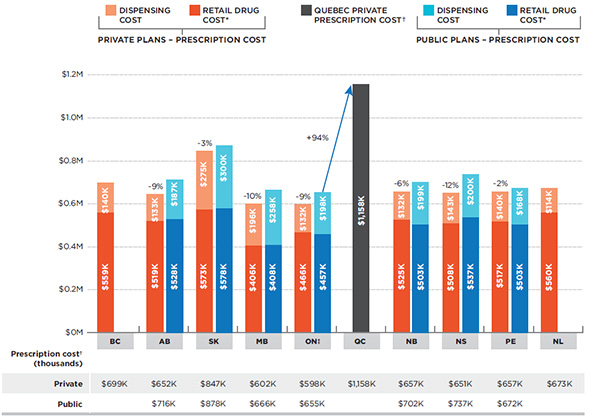

Private plans reimbursed a lower cost per prescription for generic drugs due to less frequent dispensing.

The full prescription cost is composed of both the retail drug cost and the dispensing cost. For generics, the dispensing cost may make up a sizable portion of the prescription cost, especially when small quantities of low-cost generic drugs are being dispensed. The frequency of dispensing was relatively low in private compared to public plans, as suggested by larger prescription sizes (average number of units per prescription). This resulted in fewer fees being reimbursed in private plans for the dispensing of any given quantity of drugs. Hence, in 2013 the average prescription cost was 5% to 12% lower in private compared to public plans, depending on the province.

In 2013, private plans in Quebec had low generic market shares and considerably high prescription costs relative to private and public plans in all other provinces.

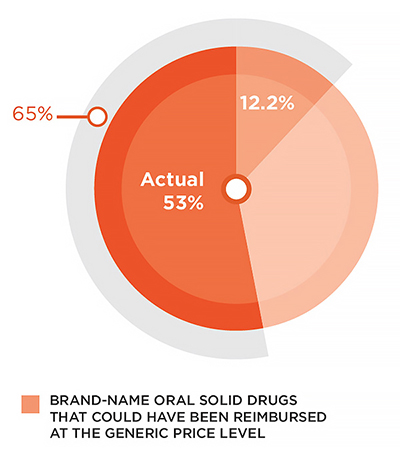

The generic share of prescriptions in Quebec was 53% in 2013, the lowest in Canada. If private plans in this province had limited the reimbursement of brand-name drugs in oral solid form to the generic price level, up to 12.2% of prescriptions would have

been impacted. This would have increased the share of prescriptions reimbursed at the generic price level to 65%, resulting in an estimated reduction of up to 6.9% in overall prescription costs.

Generic Share of prescriptions in Quebec Private Plans, 2013

Figure description

This pie graph illustrates the share of generic prescriptions for oral solid drugs in private plans in Quebec. In 2013, generic drugs represented 53% of all prescriptions. An additional 12.2% of prescriptions were for brand-name drugs with available generic equivalents. If these drugs had been reimbursed at the generic price level, this would have brought the total generic share in Quebec to 65%.

Note: Estimated results are restricted to oral solid drugs with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database.

The frequency of dispensing was a key factor in driving the prescription costs for generics in private plans in Quebec to levels 64% higher than those in Ontario. On average, 35 units of oral solid medication were dispensed per prescription in private plans

in Quebec, which was much less than the Ontario average of 64.

Note that the results of this study represent a snapshot in time with a focus on 2013. Since then, the generic market landscape in Canada has evolved in terms of both generic drug launches and policy changes.

- CIHI. 2014. Prescribed Drug Spending in Canada, 2013: A Focus on Public Drug Programs. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information, page vii.

- PMPRB. 2014. Generic Drugs in Canada, 2013. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.

- PMPRB. 2015. NPDUIS CompassRx: Annual Public Drug Plan Expenditure Report, 1st Edition. Ottawa: Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.

Introduction

While prescription drug spending represents a significant component of the overall health care costs in Canada, the annual rate of change has been gradually declining in recent years. In 2013 it reached an estimated 2.3%—the second-lowest rate in more than two decades (CIHI 2014). Generic drugs have played an important part in attenuating this growth. Many blockbuster brand-name drugs have lost patent protection and are now facing generic competition. In addition, most provincial governments have implemented generic pricing policies which have reduced the price of generic drugs in Canada and have resulted in important cost savings (Appendix B).

This report focuses on these developments from the perspective of private drug plans in Canada, providing insight into evolving generic market shares, reimbursed unit costs, as well as dispensing patterns and their impact on overall prescription costs. Results are for the 2013 calendar year, with a retrospective look at the trends since 2005. A comparative analysis with Canadian public drug plans, as well as select international markets, is also included in the report. The analysis identifies cost-saving opportunities through increased generic substitution, while highlighting the impact of dispensing patterns on the overall prescription costs for generics.

This is the first of three reports in a PMPRB series that analyzes the trends in Canadian private drug plans. Other reports will focus on cost drivers and high-cost drugs. The series provides policy makers and other stakeholders with valuable insights into the sources of cost pressures in private drug plans and identifies cost-saving opportunities.

Previous PMPRB reports have analyzed the generic market in Canada from various perspectives. A recent report concluded that Canadian generic drug price levels in 2013 continued to be higher than those of other industrialized countries (PMPRB 2014) despite the significant domestic price reductions attained through pan-Canadian efforts. Another study analyzed the cost drivers in public drug plans and found that generic substitution and price reductions exerted an important pull-down effect on drug costs in these plans in 2012/13 (PMPRB 2015).

This report is divided into six sections: Section 1 presents a brief overview of generic drug use and market shares in Canadian private and public drug plans, as well as in international markets. Through a therapeutic analysis of generic drug use, Section 2 provides further insight into the differences in market shares between private and public plans. Section 3 estimates the potential cost-savings that could be achieved through increased generic substitution. In Section 4, the average reimbursed unit costs in private markets are compared with those in public plans. Section 5 highlights the effect of prescription size on generic drug expenditures in private and public drug plans. To further illustrate the findings of the report, a case study of the top-selling generic drug atorvastatin is presented in Section 6.

Backgrounder - Private Drug Plans in Canada

Private drug plans play an important role in drug reimbursement in Canada and are key stakeholders in the health-care system.

Prescription drug costs in Canada are covered by a blend of public and private drug plans, as well as out-of-pocket payers. While all provinces and territories provide prescription drug coverage to specific population groups (typically seniors, lower-income earners or those with high drug costs in relation to their income), for the most part, private drug plans cover working-age beneficiaries and their dependants.

Drugs are only one component of the privately delivered supplementary health benefits, which also include hospital accommodation, vision care, travel insurance, paramedical services and dental care. Employers balance all of their benefits to attract and retain employees, as well as to ensure a healthy and productive workforce.

Canadians can purchase private insurance directly or they can receive coverage through their employer benefits package (the more usual option). Employers can choose different coverage structures: (i) fully insured – the risk rests with the insurer, (ii) administrative services only (A.S.O.) – the risk rests with the employer, or (iii) hybrid plans – insurer and employer share the risk.

Private plans generally cover all prescription drugs, although private formulary plans also exist. Cost sharing structures take the form of co-insurance, co-payments, deductibles, and maximums. Recent concerns over the long-term sustainability of private plans in Canada have resulted in an increased use of cost management mechanisms, such as, mandatory generic substitution, greater use of managed formularies, prior authorization and multi-tiering (promoting the use of more cost-effective medicines), preferred pharmacy networks, increased cost sharing, pooling of high-cost beneficiaries and the elimination of retiree benefits, among others.

Private insurance is the second largest market for prescribed drugs in Canada, accounting for an estimated 34.5% ($10.1 billion) of the spending in 2013 (CIHI 2014). The data reported in this study pertains to a large sample of Canadian private pay direct drug plans, covering 133 million prescriptions and $8.0 billion in total prescription cost (drug cost, markup and dispensing fees).

Methods

The main data source for this report is the IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan DatabaseFootnote 1 for the calendar years 2005 through 2013. This data is used to report on results at the national and provincial levels for the private drug plans. All Canadian provinces are included in this dataset.

The report also analyzes information contained in the National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System (NPDUIS) Database, developed by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). This database houses pan-Canadian information on public drug programs, including de-identified prescription claims-level data collected from the plans participating in the NPDUIS initiative. Results are restricted to the public drug plans whose data was available at the time of the study: Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

The MIDAS™ database from IMS AG (All Rights Reserved) is used for the international comparative analysis. The foreign markets analyzed are the seven that the PMPRB considers in reviewing the prices of patented drug products (PMPRB7): France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

The report analyzes various measures of cost. The retail drug cost includes the drug cost and markup accepted for reimbursement by the private or public plans analyzed and excludes the dispensing costs. The prescription cost includes all three cost components— drug costs, markups and dispensing costs—and is reflective of both plan-paid and patient-paid portions.

The acquisition cost is based on the average drug cost per unit accepted for reimbursement by public plans, excluding markups and dispensing costs. This is an assumed cost, as it reflects the amount accepted for reimbursement, which may differ from the amount claimed by a pharmacy.

Retail Drug Cost = Drug Cost + Markup

Prescription Cost =

Drug Cost + Markup + Dispensing Cost

Acquisition Cost =

Drug Cost in Public Plan / Units

Retail Drug Cost Per Unit =

(Drug Cost + Markup) / Units

Prescription Cost Per Unit =

(Drug Cost + Markup + Dispensing Cost) / Units

These amounts refer to what was accepted for reimbursement by the drug plans. See Appendix A for definitions.

A wholesale upcharge amount may be captured in the acquisition cost, depending on the specific reimbursement policies of each drug plan (Appendix C).

The acquisition cost is used to derive estimates of the private drug plan markups. This cost may vary between private and public plans and across provinces due to differences in the pharmacy level costs, which depend on the wholesaler upcharges and established distribution networks.

Analyses of the average cost per unit in Sections 3, 4 and 5 are restricted to oral solid drugs due to the inconsistency in unit reporting for other types of formulations (e.g., inhalers, infusions, etc.). The drugs in oral solid form account for the majority of the prescriptions (89%) for generic drugs and their related costs (91%).

The therapeutic classification used in the analysis is based on the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC). The second ATC level is reported, which relates to the therapeutic main group.

In this report the term “drug” refers to any unique combination of active ingredient, strength and form. The generic market analysis is based on the IMS Brogan and IMS MIDAS™ identifications of “generic drug”. The brand-name and generic identification available in the IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database was extended to the NPDUIS Database, CIHI.

Limitations

The results in this report represent a snapshot in time, with a focus on 2013. Since then, the generic market landscape in Canada has evolved, both in terms of additional brand-name drugs facing generic competition, and also in terms of policy changes. Specifically, the impact of recent provincial pricing policies is not fully reflected in the results (Appendix B). In addition, Bill 28Footnote 2, passed by the Quebec government, allows private plans to limit the reimbursement of brand-name drugs for which a generic exists, starting on October 1, 2015.

The comparative analysis of the average provincial retail drug cost per unit does not include private plans in Quebec, as the available retail drug cost for this province includes the dispensing cost component. Consequently, only the results for the total prescription cost are reported for private plans in Quebec.

Private drug plan data was available for all provinces; however, at the time of the study, public drug plan data was only available for Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. Comparative analyses are limited to the provinces for which both private and public drug plan data was available.

The results presented may vary by province and plan partly due to differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the active beneficiary populations. The variation in the availability of specific sub-plans in the public data also limits the comparability of the results across plans.

1. Overview of the Generic Market

The market share of generic drugs in private plans has increased markedly in recent years, from 37% in 2005 to 55% in 2013. Despite this increase, it remained lower than the market share in public plans, which was 71% in 2013. Private plans in Quebec had the lowest rate of generic use in Canada in 2013 (53%). Compared to foreign markets, Canada had one of the highest market shares of generic drugs.

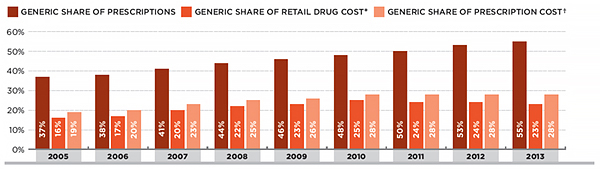

Following the loss of patent protection for many blockbuster drugs, generics have captured an increasing share of the market in recent years. Figure 1.1 reports the trend in market share for generics in private drug plans in terms of prescriptions, retail drug cost and prescription cost.

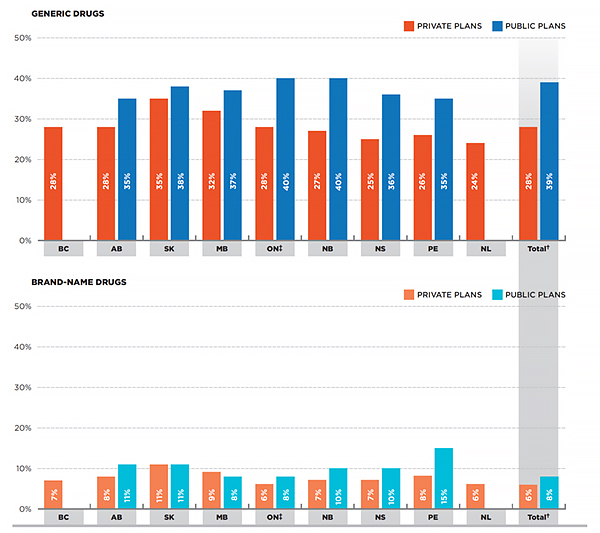

Generic drugs are generally less costly than brand-name drugs. In 2013, they accounted for 55% of prescriptions, but only 23% of the retail drug cost and 28% of the prescription cost. While the share of prescriptions for generic drugs has been increasing in recent years, the share of the retail drug cost has been on a slight decline following the implementation of provincial generic pricing policies. The generic share of the prescription cost (including dispensing costs) has remained constant since 2010, at 28%, despite the evolving market dynamics.

Figure 1.1 Generic market share in private drug plans, 2005–2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a bar graph depicting the trend in market share for generics in private drug plans in Canada in terms of prescriptions, retail drug cost and prescription cost. The generic share of prescriptions in 2005, in percent, was 37. 2006: 38; 2007: 41; 2008: 44; 2009: 46; 2010: 48; 2011: 50; 2012: 53; 2013: 55.

The generic share of retail drug cost (which includes drug cost and markup, but excludes dispensing cost) in 2005, in percent, was 16. 2006: 17; 2007: 20; 2008: 22; 2009: 23; 2010: 25; 2011: 24; 2012: 24; 2013: 23.

The generic share of prescription cost (which includes drug cost, markup and dispensing cost) in 2005, in percent, was 19; 2006: 20; 2007: 23; 2008: 25; 2009: 26; 2010: 28; 2011: 28; 2012: 28; 2013: 28.

* Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

† Includes drug cost, markup and dispensing cost.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database.

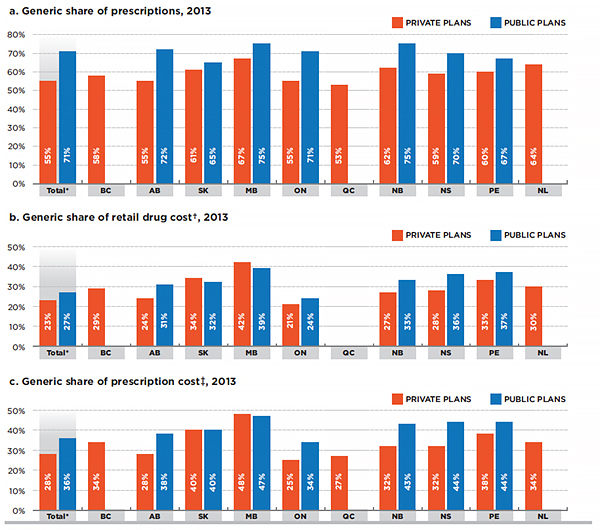

Although generic drug use in private plans has increased in recent years, in 2013, the market share of generic drugs was still lower than in public plans, 55% versus 71% of prescriptions (Figure 1.2). The generic share of retail drug costs was also lower in private plans (23%) compared to public plans (27%). The generic capture rates may vary by province and plan partly due to differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the active beneficiary populations. The variations in the availability of specific sub-plans in the public data also limit the comparability of the generic capture rates across plans.

Figure 1.2 Generic market share in private versus public drug plans, 2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a series of three bar graphs comparing the generic market share in private and public drug plans in 2013. Results are given for individual provinces as well as for the total of all provinces reported. The first graph gives the share of prescriptions; the second gives the share of retail cost; and the third gives the share of prescription cost.

a) Generic share of prescriptions, 2013

For all private plans reported, generic drugs made up 55% of the total prescriptions in 2013. For British Columbia generics represented 58% of prescriptions. In percent, Alberta: 55; Saskatchewan: 61; Manitoba: 67; Ontario: 55; Quebec: 53; New Brunswick: 62; Nova Scotia: 59; Prince Edward Island: 60; Newfoundland and Labrador: 64.

For all public plans reported, generic drugs made up 71% of the total prescriptions in 2013. For British Columbia, public drug plan data was not available. In percent, Alberta: 72; Saskatchewan: 65; Manitoba: 75; Ontario: 71; Quebec: not available; New Brunswick: 75; Nova Scotia: 70; Prince Edward Island: 67; Newfoundland and Labrador: not available.

b) Generic share of retail drug cost, 2013

For all private plans reported, the total generic share of retail drug cost (which includes drug cost and markup but excludes dispensing cost) was 23% in 2013. For British Columbia, the generic share of retail drug cost in private plans was 29%. In percent, Alberta: 24; Saskatchewan: 34; Manitoba: 42; Ontario: 21; Quebec: not available; New Brunswick: 27; Nova Scotia: 28; Prince Edward Island: 33; Newfoundland and Labrador: 30.

For all public plans reported, the total generic share of retail drug cost (which includes drug cost and markup but excludes dispensing cost) was 27% in 2013. For British Columbia, no information was available. In percent, Alberta: 31; Saskatchewan: 32; Manitoba: 39; Ontario: 24; Quebec: not available; New Brunswick: 33; Nova Scotia: 36; Prince Edward Island: 37; Newfoundland and Labrador: not available.

c) Generic share of prescription cost, 2013

For all private plans reported, the total generic share of the prescription cost (which includes drug cost, markup and dispensing cost) was 28% in 2013. For British Columbia, the generic share of prescription cost was 34%. In percent, Alberta: 28; Saskatchewan: 40; Manitoba: 48; Ontario: 25; Quebec: 27; New Brunswick: 32; Nova Scotia: 32; Prince Edward Island: 38; Newfoundland and Labrador: 34.

For all public plans reported, the total generic share of prescription cost (which includes, drug cost, markup and dispensing cost) was 36% in 2013. For British Columbia, information on the generic share of prescription cost was unavailable. By percent, Alberta: 38; Saskatchewan: 40; Manitoba: 47; Ontario: 34; Quebec: not available; New Brunswick: 43; Nova Scotia: 44; Prince Edward Island: 44; Newfoundland and Labrador: not available.

* Total results for the plans reported in this figure.

† Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

‡ Includes drug cost, markup and dispensing cost.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database;

National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

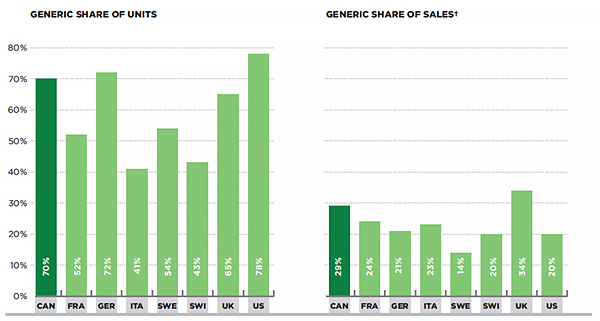

Compared to international markets, Canada had one of the highest generic utilization rates in 2013 (MIDAS™, IMS AG. All Rights Reserved). The analyzed data reflects all prescription drug sales to the pharmacy sector at manufacturer prices by country. Note that, unlike the share of prescriptions presented in Figures 1.1 and 1.2, the volume of units (physical quantities of drugs) was used to compare the international rates of generic drug use in Figure 1.3. These two measures may yield slightly different results in terms of the generic share of the market.

Figure 1.3 Generic drug market shares, Canada and the PMPRB7*, 2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This figure is composed of two bar graphs that compare the 2013 generic share of units and sales in Canada with those of the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board comparator countries.

The volume of units (physical quantities of drugs) was used as the basis for comparison. The market share of generics in Canada by units was 70%. In percent, France: 52; Germany: 72; Italy: 41; Sweden: 54; Switzerland: 43; United Kingdom: 65; United States: 78.

The market share of generics in terms of sales at the manufacturer price level in Canada was 29%. In percent, France: 24; Germany: 21; Italy: 23; Sweden: 14; Switzerland: 20; United Kingdom: 34; United States: 20.

* France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Results are restricted to the retail market (excluding hospital sales) and prescription bound products.

† At manufacturer price levels.

Data source: MIDAS™, IMS AG All Rights Reserved.

In terms of units, the market share of generics in Canada was the third highest (70%) among the seven foreign markets analyzedFootnote 3 in 2013, after Germany (72%) and the US (78%). The market share of generics in terms

of sales at the manufacturer price level is the second highest in Canada (29%), after the UK (34%). The generic share of sales by country reflects the rates of generic use relative to brand-name use, as well as the price levels for generic and brand-name drugs.

2. Therapeutic Analysis of the Generic Market

Two main factors seem to explain the relatively low generic market shares in private compared to public plans:

- The variations in the demographic and disease profiles of the beneficiary populations resulted in differences in the therapeutic mix, with a higher use of certain therapeutic categories that had limited generic availability in private plans.

- There was a greater tendency in private plans to use single-source brand-name drugs that did not have generic equivalent.

When a generic option was available, the generic substitution rates at drug level in private plans (except Quebec) closely mirrored those in public plans in 2013.

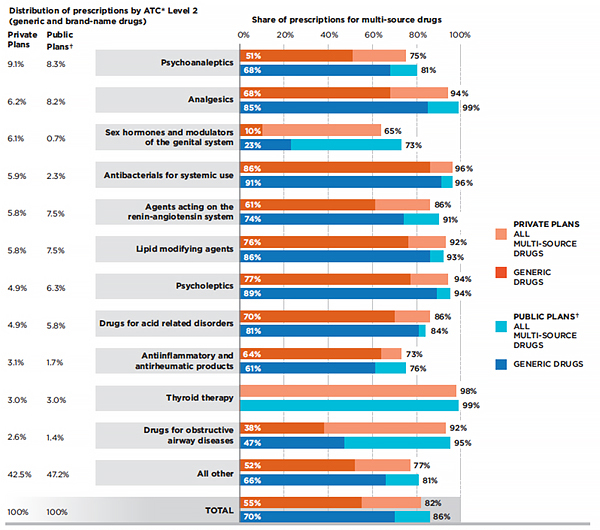

Therapeutic Mix

There are important differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the beneficiary populations in private and public plans. Figure 2.1 lists the top therapeutic classes for private and public plans along with the corresponding share of prescriptions. It also indicates the share of prescriptions for multi-source drugsFootnote 4 and the generic market share for each therapeutic class. The analysis was conducted at the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) level 2, which relates to the therapeutic main group.

The results suggest that private drug plan beneficiaries have a higher use of therapeutic classes with a relatively low share of multi-source drugs and generic penetration in both private and public plans. For example, the category of sex hormones and modulators of the

genital system accounted for 6.1% of the prescriptions in private plans and for only 0.7% in public plans in 2013. Within this category, the share of prescriptions for multi-source drugs was relatively low compared to the other categories, at 65% and 73% in private and public plans, respectively. The generic penetration was even lower at 10% and 23% in private and public plans, respectively. Similar findings are observed for obstructive airway disease drugs.

The results suggest that differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the populations in private versus public plans, as well as the availability of generics in certain therapeutic classes, result in a higher use of certain therapeutic classes with limited generic availability in private plans.

Single-Source Versus Multi-Source Drugs

Private plans tend to have a lower use of drugs that have generic availability than public plans for several important therapeutic classes. For instance, for psychoanaleptics, 75% of prescriptions were for multi-source drugs in private plans (including brand-name and generic drugs); whereas in public plans, the utilization rate was 81%. The difference of 25% and 19%, respectively, represents the share of single-source drugsFootnote 5. In other words, there seems to be a greater tendency to use drugs without generic availability in private plans.

Figure 2.1 Generic market share of prescriptions for multi-source drugs for top therapeutic classes — Private and public plans, 2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This bar graph lists the top therapeutic classes for private and public drug plans in Canada in 2013 along with the corresponding share of prescriptions. Therapeutic divisions correspond to the World Health Organization Anatomical, Therapeutic, Chemical classification system level 2. The graph indicates the share of prescriptions for multi-source drugs and the generic market share for each therapeutic class. Note that the public drug plan data was from Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Under private plans, psychoanaleptics represented 9.1% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 75%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 51%.

Under public plans, psychoanaleptics represented 8.3% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 81%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 68%.

Under private plans, analgesics represented 6.2% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 94%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 68%.

Under public plans, analgesics represented 8.2% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 99%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 85%.

Under private plans, sex hormones and modulators of the genital system represented 6.1% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 65%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 10%.

Under public plans, sex hormones and modulators of the genital system represented 0.7% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 73%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 23%.

Under private plans, antibacterials for systemic use represented 5.9% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 96%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 86%.

Under public plans, antibacterials for systemic use represented 2.3% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 96%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 91%.

Under private plans, agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system represented 5.8% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 86%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 61%.

Under public plans, agents acting on the renin-angiotensin system represented 7.5% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 91%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 74%.

Under private plans, lipid modifying agents represented 5.8% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 92%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 76%.

Under public plans, lipid modifying agents represented 7.5% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 93%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 86%.

Under private plans, psycholeptics represented 4.9% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 94%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 77%.

Under public plans, psycholeptics represented 6.3% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 94%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 89%.

Under private plans, drugs for acid related disorders represented 4.9% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 86%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 70%.

Under public plans, drugs for acid related disorders represented 5.8% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 84%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 81%.

Under private plans, anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic products represented 3.1% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 73%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 64%.

Under public plans, anti-inflammatory and anti-rheumatic products represented 1.7% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 76%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 61%.

Under private plans, thyroid therapy represented 3.0% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 98%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 0%.

Under public plans, thyroid therapy represented 3.0% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 99%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 0%.

Under private plans, drugs for obstructive airway diseases represented 2.6% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 92%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 38%.

Under public plans, drugs for obstructive airway diseases represented 1.4% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 95%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 47%.

Under private plans, all other drugs represented 42.5% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 77%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 52%.

Under public plans, all other drugs represented 47.2% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 81%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 66%.

Under private plans, total drugs represented 100% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 82%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 55%.

Under public plans, total drugs represented 100% of prescriptions in 2013. The share of prescriptions for all multi-source drugs was 86%; the share of prescriptions for generic drugs was 70%.

* Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification system maintained by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology.

† Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database;

National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

These variations may be due to differences in the disease profiles of the populations, as single-source and multi-source drugs within a therapeutic group may be used to treat different indications. Variations in drug coverage between private and public plans through the use of formularies may also play a role. These aspects, however, are not assessed in this study.

Note that the single-source generics, which account for a small market share, are not captured in the results presented in Figure 2.1. Hence, the 70% total multi-source generic market share is correspondingly lower than the 71% market share for generics reported in Figure 1.2.

Generic Substitution

When analyzing the drugs that have generic availability, the generic capture rate is lower in private than in public plans. For instance, 51% of the prescriptions for psychoanaleptic drugs reimbursed by private plans were for generic multi-source drugs; whereas, in public

plans, the generic capture rate was 68% in 2013 (Figure 2.1). Similar results are observed in many other classes.

A closer look at individual molecules and their province-specific generic market shares indicates that, generally, private plans Quebec had the lowest generic substitution rates in 2013. This partly explains the lower generic market shares in private compared to public plans. Private plans in other provinces more closely mirrored the generic penetration in public plans.

Table 2.1 compares the generic market shares in private and public plans for 10 top-selling molecules. For instance, for atorvastatin calcium, which accounted for the largest share of generic costs in 2013, the capture rate for the generic version was 84.8% in private plans in Quebec, 92.1% in other private plans and 96.0% in public plans. The brand-name product Lipitor accounted for the remaining shares. Similar findings were observed for all other top 10 drugs.

Table 2.1 Generic market share for top 10 generic drugs* — Private versus public plans, 2013

|

Generics share of prescriptions |

Generics share of retail drug cost† |

| Quebec Private Plans |

Other Private Plans |

Public Plans† |

Quebec Private Plans |

Other Private Plans |

Public Plans† |

| 1 |

Atorvastatin calcium |

84.8% |

92.1% |

96.0% |

63.8% |

75.9% |

93.2% |

| 2 |

Rosuvastatin calcium |

70.1% |

81.2% |

88.6% |

46.9% |

62.4% |

84.5% |

| 3 |

Pantoprazole sodium |

89.7% |

96.2% |

99.4% |

76.7% |

87.3% |

98.0% |

| 4 |

Venlafaxine hydrochloride |

80.5% |

94.8% |

98.1% |

60.7% |

82.1% |

95.5% |

| 5 |

Zopiclone |

90.8% |

97.1% |

99.6% |

79.5% |

90.8% |

99.1% |

| 6 |

Amlodipine besylate |

86.5% |

93.7% |

96.9% |

69.2% |

79.5% |

94.4% |

| 7 |

Metformin hydrochloride |

91.1% |

89.9% |

94.5% |

75.2% |

62.5% |

91.1% |

| 8 |

Citalopram hydrobromide |

86.2% |

96.9% |

99.1% |

73.3% |

91.8% |

97.9% |

| 9 |

Ramipril |

85.8% |

97.9% |

99.4% |

69.2% |

91.4% |

98.6% |

| 10 |

Valacyclovir hydrochloride |

86.8% |

96.0% |

98.2% |

73.0% |

88.2% |

97.3% |

* Top generic drugs based on retail drug cost levels in 2013. The analysis was restricted to generic drugs with brand availability.

† Includes the drug cost and markup; excludes the dispensing cost.

‡ Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database;

National Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

While at drug-level, the generic substitution rates were generally high in private and public plans, they varied across drugs. A drug-mix component may also have played a role in the relatively low generic market shares in private compared to public plans, as drugs with higher generic penetration may have been used more in public plans.

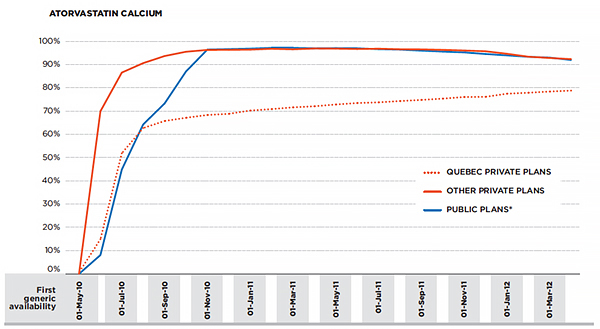

Figure 2.2 provides a more detailed analysis of the monthly uptake in the market share for generic atorvastatin calcium over a 24-month period. After an initial uptake period, the generic capture rate in most private and public plans was very high, reaching an average of 97%. Toward the end of the period analyzed, the generic capture rates have been on a gradual decline, principally due to the influence of the private and public plans in Ontario. A discussion on loyalty cards, which may explain this trend, is provided in the next section.

Figure 2.2 Generic share of units for atorvastatin calcium, private and public drug plans

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a line graph depicting the generic share of units for atorvastatin calcium in Quebec private plans, other Canadian private plans and Canadian public drug plans from May 1, 2010, to April 1, 2012. On May 1, 2010, there was no the generic market share of units for atorvastatin calcium in any of the plans. All shares are expressed as percentages.

June 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 15; other private plans; 70; public plans: 8.

July 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 52; other private plans: 87; public plans: 45.

August 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 63; other private plans: 91; public plans: 64.

September 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 66; other private plans: 94; public plans: 73.

October 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 67; other private plans: 95; public plans: 87.

November 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 68; other private plans: 96; public plans: 96.

December 1, 2010 – Quebec private plans: 69; other private plans: 96; public plans: 97.

January 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 70; other private plans: 96; public plans: 97.

February 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 71; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

March 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 72; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

April 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 72; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

May 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 73; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

June 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 73; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

July 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 74; other private plans: 97; public plans: 97.

August 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 74; other private plans: 97; public plans: 96.

September 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 75; other private plans: 97; public plans: 96.

October 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 75; other private plans: 96; public plans: 96.

November 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 76; other private plans: 96; public plans: 95.

December 1, 2011 – Quebec private plans: 76; other private plans: 96; public plans: 95.

January 1, 2012 – Quebec private plans: 77; other private plans: 95; public plans: 94.

February 1, 2012 – Quebec private plans: 78; other private plans: 93; public plans: 93.

March 1, 2012 – Quebec private plans: 78; other private plans: 93; public plans: 93.

April 1, 2012 – Quebec private plans: 79; other private plans: 92; public plans: 92.

* Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Data Source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database; National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Private plans in Quebec are the notable exception—the uptake was more gradual, as it took two years for the generic molecule to capture nearly 80% of the market.

An in-depth analysis of the prescription costs related to atorvastatin calcium in 2013 in private and public plans is provided in Section 6.

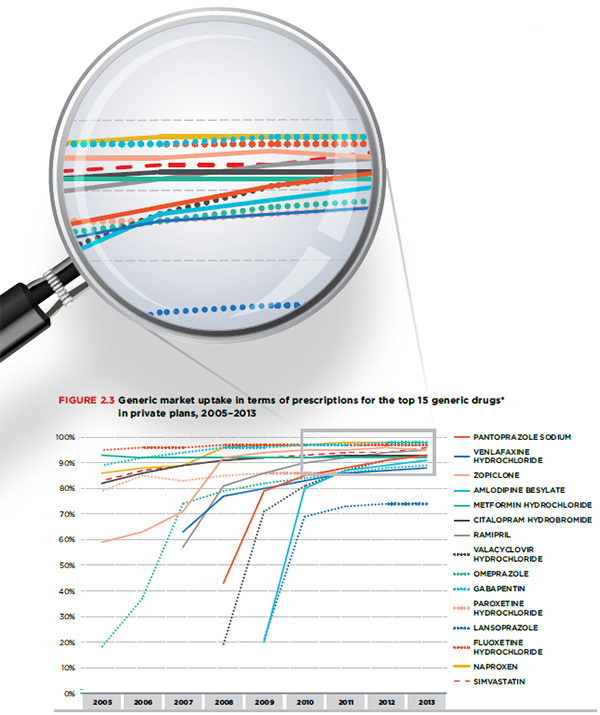

In recent years, the use of mandatory generic substitutionFootnote 6 has increased in private plans, mirroring the policies already in effect in public drug plans (Lynas 2012). An analysis of the top 15 established generic molecules (available since 2008 or earlier) demonstrates the generic uptake effect of these policies, pointing toward an increased generic market share in recent years for established molecules (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Generic market uptake in terms of prescriptions for the top 15 generic drugs* in private plans, 2005–2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a line graph depicting the generic market uptake in terms of prescriptions for the top 15 generic drugs in Canadian private plans between 2005 and 2013. Top generic drugs were determined based on their retail cost levels in 2013. The analysis was restricted to established generic molecules (available since 2008 or earlier) with brand availability.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of simvastatin was 83%. In percent, 2006: 87; 2007: 89; 2008: 91; 2009: 92; 2010: 93; 2011: 94; 2012: 94; 2013: 96.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of naproxen was 86%. In percent, 2006: 88; 2007: 89; 2008: 96; 2009: 97; 2010: 97; 2011: 98; 2012; 98; 2013: 98.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of fluoxetine hydrochloride was 95%. In percent, 2006: 96; 2007: 96; 2008: 97; 2009: 97; 2010: 97; 2011: 97; 2012: 97; 2013: 97.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of lansoprazole was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: not available; 2008: not available; 2009: 21; 2010: 69; 2011: 73; 2012: 74; 2013: 74.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of paroxetine hydrochloride was 79%. In percent, 2006: 85; 2007: 83; 2008: 85; 2009: 86; 2010: 86; 2011: 86; 2012: 87; 2013: 88.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of gabapentin was 89%. In percent, 2006: 92; 2007: 94; 2008: 96; 2009: 96; 2010: 97; 2011: 97; 2012: 98; 2013: 98.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of omeprazole was 18%. In percent, 2006: 37; 2007: 74; 2008: 79; 2009: 82; 2010: 84; 2011: 86; 2012: 88; 2013: 89.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of valacyclovir hydrochloride was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: not available; 2008: 19; 2009: 71; 2010: 81; 2011: 87; 2012: 91; 2013: 93.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of ramipril was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: 57; 2008: 81; 2009: 86; 2010: 90; 2011: 92; 2012: 94; 2013: 95.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of citalopram hydrobromide was 82%. In percent, 2006: 86; 2007: 89; 2008: 91; 2009: 92; 2010: 92; 2011: 93; 2012: 93; 2013: 93.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of metformin hydrochloride was 93%. In percent, 2006: 92; 2007: 92; 2008: 92; 2009: 92; 2010: 92; 2011: 92; 2012: 92; 2013: 92.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of amlodipine besylate was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: not available; 2008: not available; 2009: 20; 2010: 80; 2011: 87; 2012: 89; 2013: 91.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of zopiclone was 59%. In percent, 2006: 63; 2007: 71; 2008: 92; 2009: 94; 2010: 95; 2011: 95; 2012: 96; 2013: 95.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of venlafaxine hydrochloride was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: 63; 2008: 77; 2009: 80; 2010: 83; 2011: 86; 2012: 87; 2013: 88.

In 2005, the generic market uptake of pantoprazole sodium was not available. In percent, 2006: not available; 2007: not available; 2008: 43; 2009: 79; 2010: 85; 2011: 88; 2012: 91; 2013: 93.

* Top generic drugs were determined based on their retail cost levels in 2013. The analysis was restricted to established generic molecules (available since 2008 or earlier) with brand availability.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database.

3. Generic Cost Saving Opportunities

Closing the gap between the generic market shares at drug level in private and public plans would have resulted in marginal cost savings for most private plans, as their generic capture rates were already closely aligned with those in public plans. The notable exception is Quebec, where an increase in the generic capture rates to mirror those prevailing in public plans would have resulted in a marked increase in the generic market share (6.6%) and important cost savings (4.3% of the overall prescription cost).

On the other hand, if private plans across Canada had limited the reimbursement of brand-name drugs in oral solid form to the generic price level, as in public plans, up to 9.6% of prescriptions for brand-name products would have been reimbursed at the generic price level, representing cost savings of up to 5.7% of the overall retail drug costs.

This section explores two scenarios that may allow private plans to take an increased advantage of the current generic competition:

(i) Substituting brand-name products for their generic version to the same extent as public plans

Figure 3.1 reports the provincial variations in the estimated generic market share for private plans if they had had the same generic capture rates as public plans at the individual drug level. The analysis assumes, for instance, that in the case of atorvastatin calcium reported in Table 2.1, the market share in private plans for Quebec would have increased from 84.8% to 96.0%, equalling the market share in public plans. A similar assumption was applied for all oral solid drugs with over 1,000 annual prescriptions used in both private and public plans.

The results suggest that the overall generic market shares for private plans would have increased to 59%, resulting in an estimated reduction of 2.7% in overall retail drug costs, equating to an average cost saving of $12,873 per 1,000 beneficiaries. Most of these savings would have been realized by private plans in Quebec.

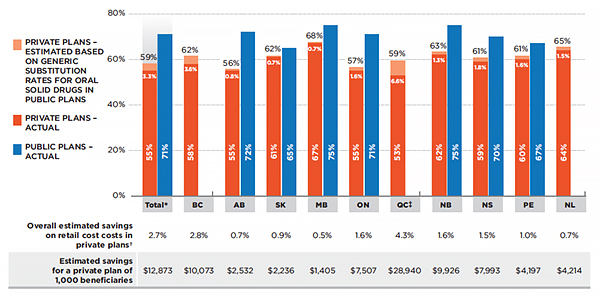

Figure 3.1 Generic market share of prescriptions, private and public plans — Actual and estimated based on the generic substitution rates for oral solid drugs in public plans, 2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This bar graph depicts the provincial variations in the generic market share of prescriptions for Canadian public and private plans in 2013. Shares for individual provinces are included as well as the total for all provinces reported. In particular, the graph gives the actual market share for private plans as well as the estimated share if the private plans had had the same generic capture rates as the public plans at the individual drug level for oral solid drugs with both generic and brand-name availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions.

The estimated total generic market share of prescriptions for private plans, estimated based on generic substitution rates for oral solid drugs in public plans, is 59%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans is 55%, a difference of 3.3%. The total, actual generic market share of prescriptions for public plans is 71%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in British Columbia is 62%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in British Columbia is 58%, a difference of 3.6%. No data was available for prescriptions under public plans in British Columbia.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Alberta is 56%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Alberta is 55%, a difference of 0.8%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Alberta is 72%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Saskatchewan is 62%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Saskatchewan is 61%, a difference of 0.7%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Saskatchewan is 65%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Manitoba is 68%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Manitoba is 67%, a difference of 0.7%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Manitoba is 75%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Ontario is 57%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Ontario is 55%, a difference of 1.6%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Ontario is 71%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Quebec is 59%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Quebec is 53%, a difference of 6.6%. Estimates for Quebec are based on the prescription cost, including the drug cost, markup and dispensing cost. There is no information available on the generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Quebec.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in New Brunswick is 63%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in New Brunswick is 62%, a difference of 1.3%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in New Brunswick is 75%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Nova Scotia is 61%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Nova Scotia is 59%, a difference of 1.8%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Nova Scotia is 70%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Prince Edward Island is 61%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Prince Edward Island is 60%, a difference of 1.6%. The generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Prince Edward Island is 67%.

The estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Newfoundland and Labrador is 65%. The actual generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in Newfoundland and Labrador is 64%, a difference of 1.5%. There is no information available on the generic market share of prescriptions under public plans in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Below the bar graph, a corresponding table gives the overall estimated savings on retail costs in private plans as well as the estimated savings for a private plan of 1,000 beneficiaries for each of the provinces and the total of all provinces reported. The savings represent the difference between the actual and estimated generic market share for each market.

In total, the overall estimated savings on retail costs (which includes drug cost and markup, but excludes dispensing cost) in private plans was 2.7%. In percent, British Columbia: 2.8; Alberta: 0.7; Saskatchewan: 0.9; Manitoba: 0.5; Ontario: 1.6; Quebec: 4.3; New Brunswick: 1.6; Nova Scotia: 1.5; Prince Edward Island: 1.0; Newfoundland and Labrador: 0.7.

In total, the estimated savings for a private plan of 1,000 beneficiaries, in dollars, was 12,873. British Columbia: 10,073; Alberta: 2,532; Saskatchewan: 2,236; Manitoba: 1,405; Ontario: 7,507. Quebec: 28,940; New Brunswick: 9,926; Nova Scotia: 7,993; Prince Edward Island: 4,197; Newfoundland and Labrador: 4,214.

Note: Estimated results are restricted to oral solid drugs with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions.

* Total results for the plans reported in this figure.

† Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

‡ Estimates for Quebec are based on the prescription cost, including the drug cost, markup and dispensing cost.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database; National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

For the private plans in British Columbia, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador, the generic capture rates are based on the rates for all public plans analyzed, as provincial-specific public drug plan data for these provinces was not available at the time of the analysis.

Note that even if private plans substituted brand-name drugs for the generic versions to the same extent as the public plans, the generic market share in private plans would have climbed by only 3.3% up to 59%, still remaining lower than in public plans (71%). This is due to inherent differences in the public and private markets. Differences in the demographic and disease profiles of the beneficiary populations may translate into a different share or mix of generic drugs being used (methadone, for instance, is used more in public than in private plans).

This scenario, however, does not take into account the fact that public plans actually reimburse brand-name drugs with generic availability at levels close to the generic cost levels due to mandatory generic substitutionFootnote 7 (Figure 3.2). In the case of atorvastatin calcium, this would apply to the 4.0% of the prescriptions for the brand-name Lipitor, as 96.0% of the prescriptions were for generics.

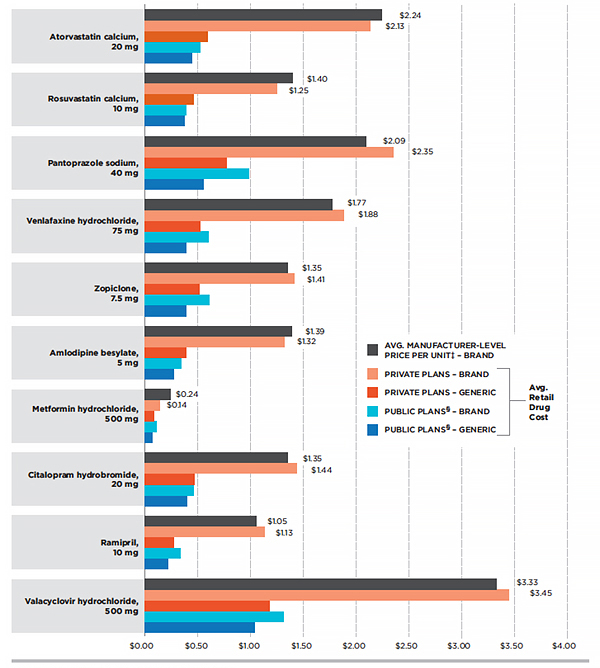

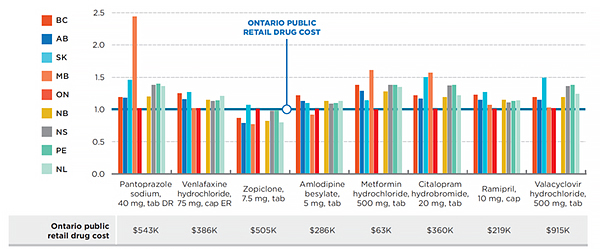

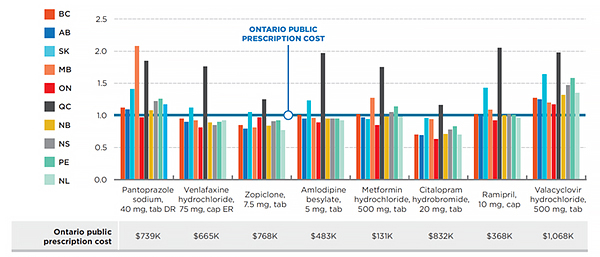

Figure 3.2 Average retail drug cost* per unit for the top 10 selling generic drugs† in private plans, 2013 (largest utilized strength–form combination)

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a bar graph depicting the average retail drug cost per unit for the top 10 selling generic drugs in private plans in 2013. Determination of the average retail drug cost included the drug cost and markup, but excluded the dispensing cost. The top generic drugs were selected based on retail drug cost levels in 2013. Public plan data were taken from Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

For brand-name atorvastatin calcium, 20 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 2.24. Brand name under private plans: 2.13; generic under private plans: 0.59; brand name under public plans: 0.52; generic under public plans: 0.44.

For brand-name rosuvastatin calcium, 10 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.40. Brand name under private plans: 1.25; generic under private plans: 0.46; brand name under public plans: 0.39; generic under public plans: 0.37.

For brand-name pantoprazole sodium, 40 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 2.09. Brand name under private plans: 2.35; generic under private plans: 0.77; brand name under public plans: 0.98; generic under public plans: 0.55.

For brand-name venlafaxine hydrochloride, 75 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.77. Brand name under private plans: 1.88; generic under private plans: 0.52; brand name under public plans: 0.60; generic under public plans: 0.39.

For brand-name zopiclone, 7.5 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.35. Brand name under private plans: 1.41; generic under private plans: 0.51; brand name under public plans: 0.61; generic under public plans: 0.39.

For brand-name amlodipine besylate, 5 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.39. Brand name under private plans: 1.32; generic under private plans: 0.39; brand name under public plans: 0.34; generic under public plans: 0.27.

For brand-name metformin hydrochloride, 500 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 0.24. Brand name under private plans: 0.14; generic under private plans: 0.08; brand name under public plans: 0.11; generic under public plans: 0.07.

For brand-name citalopram hydrobromide, 20 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.35. Brand name under private plans: 1.44; generic under private plans: 0.47; brand name under public plans: 0.46; generic under public plans: 0.40.

For brand-name ramipril, 10 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 1.05. Brand name under private plans: 1.13; generic under private plans: 0.27; brand name under public plans: 0.33; generic under public plans: 0.22.

For brand-name valacyclovir hydrochloride, 500 mg, the average manufacturer-level price per unit (excluding markups and dispensing costs) in dollars was 3.33. Brand name under private plans: 3.45; generic under private plans: 1.18; brand name under public plans: 1.31; generic under public plans: 1.04.

* Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

† Top generic drugs based on retail drug cost levels in 2013. The analysis was restricted to generic drugs with brand availability.

‡ Excludes markups and dispensing costs.

§ Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island.

Data source: MIDAS™, IMS AG All Rights Reserved; IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database; National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

In private plans, on the other hand, brand-name drugs with a genericized molecule were reimbursed at unit cost levels comparable or slightly lower than the average manufacturer unit price (Figure 3.2). Note that the average retail drug cost includes the markup, whereas the average manufacturer unit price excludes the markup components (wholesale and pharmacy). For drugs with a lower average retail cost, a portion of the prescriptions may have been reimbursed by private plans with mandatory generic substitution, limiting the reimbursement to the generic unit price level.

Loyalty Cards

The retail costs reported in this analysis do not include amounts paid through manufacturer-issued patient reimbursement loyalty cards, also referred to as drug discount cards or coupons.

Loyalty cards are offered to patients by some brand-name manufacturers for some drugs, and can be used to cover the cost difference related to the purchase of a brand-name product.

Drug plans that have mandatory generic substitution* reimburse brand-name drugs with generic availability at the generic cost level. If the beneficiary uses a loyalty card, the drug manufacturer covers the difference in cost between the brand-name and the generic drug. The amounts paid using loyalty cards may be reimbursed through the adjudication process as a coordination-of-benefits (COB) or through a direct refund by Visa debit card.

In drug plans that do not have mandatory generic substitution, loyalty cards have no bearing on the amount that the private plans will accept for reimbursement, i.e., brand-name products are reimbursed at the brand-name price level. The use of loyalty cards may result in a reduced generic market share, as brand-name drugs are able to retain or gain market share. While the generic market share for drugs with generic availability may be determined by pharmacy practice of dispensing generic drugs, this may be influenced by the beneficiaries requesting the brand-name drug through the use of loyalty cards.

The IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database does not flag the plans that have mandatory generic substitution or the prescriptions for which a loyalty card may have been used. The retail costs reported reflect the amounts accepted for reimbursement by private plans. In the case of plans with mandatory generic substitution this would be limited to the generic price level. The data does not include COB claims, meaning that amounts reimbursed by a secondary payer or through loyalty cards by manufacturers are not captured.

As indicated in Figure 3.2, the average retail cost for brand-name drugs in private plans for top-selling molecules with generic availability was lower than the average manufacturer unit price. This suggests that a portion of the prescriptions reimbursed by private plans had mandatory generic substitution and were capped at the generic price level. However, the portion of these prescriptions that was partly paid through loyalty cards cannot be determined.

*Mandatory generic substitution is a drug plan feature that encourages beneficiaries to utilize the lower cost interchangeable generic drugs by limiting the reimbursement of the brand-name drugs to the generic price level.

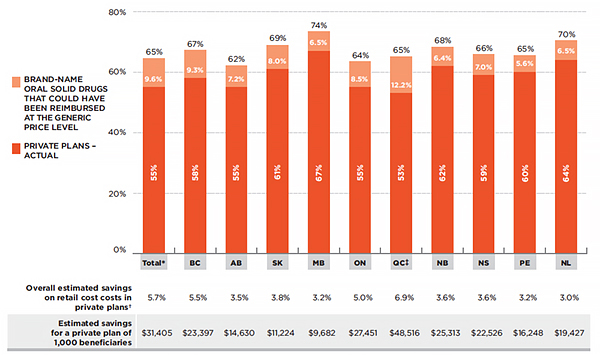

(ii) Limiting the reimbursement of brand-name drugs to the generic price level

If private plans across Canada had limited the reimbursement of brand-name drugs in oral solid form to the generic price level, as in public plans (complete generic mandatory substitution), up to 9.6% of the prescriptions would have been impacted in 2013, resulting in a total of 65% of the prescriptions in private plans being reimbursed at the generic price level. This would have generated up to an estimated 5.7% reduction in overall retail drug costs, representing a cost savings of up to $31,405 per average plan of 1,000 beneficiaries. Figure 3.3 reports on provincial variations in these results.

Figure 3.3 Generic market share of prescriptions, private plans — Actual and estimated share based on mandatory generic substitution for oral solid drugs in all plans, 2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This is a bar graph depicting the actual and estimated generic market share of prescriptions under private plans in 2013. Estimated values are based on mandatory generic substitution for all oral solid drugs (with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions) that could have been reimbursed at the generic price level. Shares for individual provinces are included, as well as the total for all provinces reported.

In total, the actual generic market share for prescriptions of oral solid drugs under private plans was 55%. The estimated share of brand-name oral solid drugs that could be reimbursed at the generic price level is 65%, an increase of 9.6%.

In British Columbia, the actual generic market share was 55%. The estimated share was 67%, an increase of 9.3%.

In Alberta, the actual generic market share was 55%. The estimated share was 62%, an increase of 7.2%.

In Saskatchewan, the actual generic market share was 61%. The estimated share was 69%, an increase of 8.0%.

In Manitoba, the actual generic market share was 67%. The estimated share was 74%, an increase of 6.5%.

In Ontario, the actual generic market share was 55%. The estimated share was 64%, an increase of 8.5%.

In Quebec, the actual generic market share was 53%. The estimated share was 65%, an increase of 12.2%. Estimates for Quebec are based on the prescription cost, including the drug cost, markup and dispensing cost.

In New Brunswick, the actual generic market share was 62%. The estimated share was 68%, an increase of 6.4%.

In Nova Scotia, the actual generic market share was 59%. The estimated share was 66%, an increase of 7.0%.

In Prince Edward Island, the actual generic market share was 60%. The estimated share was 65%, an increase of 5.6%.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the actual generic market share was 64%. The estimated share was 70%, an increase of 6.5%.

Below the bar graph, a corresponding table gives the overall estimated savings on retail costs in private plans as well as the estimated savings for a private plan of 1,000 beneficiaries for each of the provinces and the total of all provinces reported. The savings represent the difference between the actual and estimated generic market share for each market.

In total, the overall estimated savings on retail cost costs in private plans (includes drug cost and markup, but excludes dispensing cost) was 5.7%. In percent, British Columbia: 5.5; Alberta: 3.5; Saskatchewan: 3.8; Manitoba: 3.2; Ontario: 5.0; Quebec: 6.9; New Brunswick: 3.6; Nova Scotia: 3.6; Prince Edward Island: 3.2; Newfoundland and Labrador: 3.0.

In total, the estimated savings for a private plan of 1,000 beneficiaries in dollars was 31,405; British Columbia: 23,397; Alberta: 14,630; Saskatchewan: 11,224; Manitoba: 9,682; Ontario: 27,451; Quebec: 48,516; New Brunswick: 25,313; Nova Scotia: 22,526; Prince Edward Island: 16,248; Newfoundland and Labrador: 19,427.

Note: Estimated results are restricted to oral solid drugs with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions.

* Total results for the plans reported in this figure.

† Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

‡ Estimates for Quebec are based on the prescription cost, including the drug cost, markup and dispensing cost.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database; National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Private plans in Quebec could have benefitted the most from cost savings through increased generic substitution. If they had implemented mandatory generic substitution in all plans in 2013, up to 12.2% of prescriptions for brand-name products would have been substituted for their generic versions, increasing the generic market share to 65% and resulting in an estimated 6.9% reduction in overall prescription costs.

The assessment of generic cost saving opportunities provided in this section was restricted to drugs in oral solid form due to the inconsistency in unit reporting for other types of formulations (e.g., inhalers, infusions, etc.). The potential savings may actually be much higher if mandatory generic substitution was extended to drugs in non-oral solid form.

These results represent a snapshot in time as of 2013. Since then, the generic market landscape in Canada has evolved, both in terms of additional brand-name drugs facing generic competition and in terms of policy changes. In particular, Bill 28Footnote 8, passed by the Quebec government, allows private plans to limit the reimbursement for brand-name drugs for which a generic exists, starting on October 1, 2015.

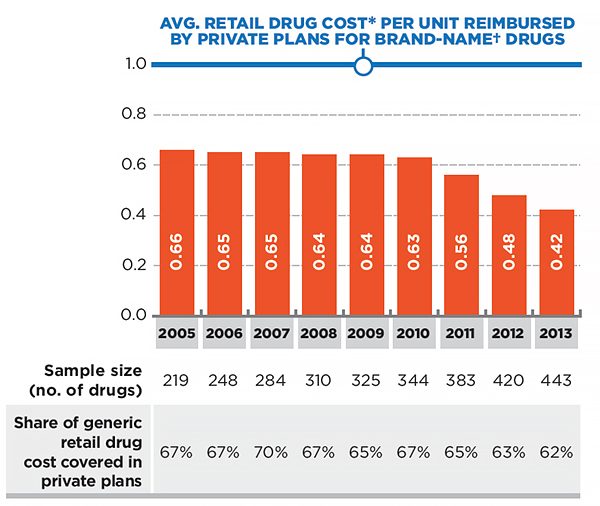

4. Retail Drug Costs of Generic Drugs

Generic pricing policies introduced by most provincial governments since 2010 markedly reduced the prices of generic drugs reimbursed by private plans, from 0.63 of the brand-reference in 2010 to 0.42 in 2013. This has resulted in important cost savings, ranging from 8% to 13% of the overall retail drug cost in private plans in 2013.

At the provincial level, private and public plans reimbursed comparable average retail drug costs per unit for generic drugs. Interprovincial variations reflect the evolving provincial generic pricing policies.

From 2005 to 2010, the average generic retail drug cost per unit in private plans across Canada was stable, ranging from 0.63 to 0.66 of the reference-brand level (Figure 4.1). However, since 2011, generic prices have been on decline, as most provincial governments implemented generic pricing policies which have reduced the price of generic drugs in all markets, including private plans. Consequently, by 2013, generic prices reached a low of 0.42 of the reference-brand level.

Figure 4.1 Generic-to-brand average retail drug cost per unit in private plans, 2005–2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This bar graph depicts the trend in the generic-to-brand ratio for the average retail drug cost per unit in Canadian private plans from 2005 to 2013. The brand-name average retail drug cost per unit in the year prior to the generic entry was used as a reference to determine the relative generic cost level for all the years following generic entry.

Ratios of generic-to-brand retail cost are given per year. 2005: 0.66; 2006: 0.65; 2007: 0.65; 2008: 0.64; 2009: 0.64; 2010: 0.63; 2011: 0.56; 2012: 0.48; 2013: 0.42.

The number of drugs (sample size) and corresponding share of the retail drug cost covered by the private plans are given in a table under the bar graph.

Number of drugs by year is 2005; 219; 2006: 248; 2007: 284; 2008: 310; 2009: 325; 2010: 344; 2011: 383; 2012: 420; 2013: 443.

Share of generic retail drug cost, in percent, by year is 2005: 67; 2006: 67; 2007: 70; 2008: 67; 2009: 65; 2010: 67; 2011: 65; 2012: 63; 2013: 62.

Note: Results are restricted to oral solid drugs with both brand and generic availability, with over 1,000 annual prescriptions and that are used in all provinces.

* Includes drug cost and markup; excludes dispensing cost.

† The brand-name average retail drug cost per unit in the year prior to generic entry was used as a reference to determine the relative generic cost level for all the years following generic entry.

Data source: IMS Brogan Private Pay Direct Drug Plan Database.

The average retail drug cost per unit relative to the brand-name cost reimbursed by private plans has decreased in all provinces, from a range of 0.58–0.67 in 2010 to a range of 0.36–0.45 in 2013. These reductions reflect the implementation of provincial generic pricing policies, which have resulted in significant cost savings. Specifically, in 2013, cost reductions for the 443 drugs analyzed in this report (which accounted for 62% of the generic retail drug costs in 2013) resulted in estimated savings in the range of 8–13% of the total retail drug cost, depending on the province.

The extent of the savings is a function of the decrease in the generic retail drug cost per unit, as well as the generic share of the overall retail drug cost in the market (Figure 1.2). For example, the impact on the Ontario private market is dependent on the fact that not only

does this province has some of the lowest retail drug cost levels for generics, but also that the Ontario private plans have one of the lowest rates of generic use (Figure 1.2).

The results in Figure 4.1 and 4.2 were restricted to multi-source drugs in oral solid form with both brand and generic availability and with over 1,000 annual prescriptions. Note that the sample size of the drugs analyzed increased over time, from 219 drugs in 2005 to 433 in 2013, reflecting the increased availability of generic drugs. These drugs accounted for 62% of the generic retail drug costs in 2013.

Figure 4.2 Province-specific ratio of generic-to-brand average retail drug cost per unit for generic drugs — Private plans, 2005–2013

Click on image for larger view

Figure description

This bar graph depicts the trend in the average ratio of the generic-to-brand retail drug cost per unit for generic drugs in select provincial private plans from 2005 to 2013. This was based on a sample size of 344 drugs in 2010 and 443 drugs in 2013.